The many meanings of reading (3). Speed.

The term 'to read' is used for a myriad of activities. In this series, I will explore the different uses of the word in the context of book history. In this third instalment: speed.

We read slow when learning how to read, Alphabet book, Alexandre Nikolayevich Benois 1904.

One of the scarcest resources involved in reading is time. Besides playing a role on how many texts one can read in a life span, time is also a factor when we are learning to read. Acquiring the skill involves a lengthy process of learning the alphabet, coupling letters to sounds, then to syllables and words, and finally to complex meanings. We could assume that the pace of reading depends on how well one has mastered these competences, however the speed in which people read and have read is also influenced by other factors.

One text is not the other

Reading the Bible (Our Daily Bread), Hand, Bible, Religion image, Celiosilveira, pixabay, 2014.

As mentioned in my first post, the forms and manners of reading have changed due to several factors such as the type and amount of texts available, the places where the activity took place, and the purpose of it. For example, Margarita reading a sacred text differs from Hayden reading a book for an essay due next week. The former demands careful and slow reading as this is part of a religious practice, while in the latter Hayden might seek to finish his task as soon as possible to enjoy the weekend.

The slow change of speed

When we humans started reading we did so out loud and thus the speed was influenced by specific circumstances. For example, the way a text was written. Did it have enough spacing between the words, and was the script clear? Undoubtedly, it also depended on how skilful the reader was. However there is a limit on how fast one can read out loud, specially if reading to others.

The speed changed slowly through time as people started reading silently and abbreviations, punctuation signs, and spaces in between words were included. Yet the change did not permeate to all classes due to several reasons. First of all, there was the issue of book supply. The amount of texts available in the Antiquity and during the Middle Ages was smaller compared to later historical periods, and so the actual amount of books to read was limited.

Another factor which played a role was the type of text. For example, a religious book is usually read in a more focused and slow fashion. Finally, the reader and his goals also influenced the speed, even during the Middle Ages. A scholar reading several treatises would use a faster pace than a layperson reading a book of hours. This context changed gradually when more and different texts became available and education was opened to larger groups in society.

Speed as a necessity

“the life of a man, however prolonged, is hardly

sufficient for reading [all of the history books]”

In 1566, Jean Bodin, a French jurist and political philosopher, complained about the very many books available on one subject alone (see quote above). The invention of the printed press brought with it the anxiety for an overabundance of books, so that many felt it was humanly impossible to catch up with everything being written on top of “having to” read the classics. As a solution, some authors published even more books with strategies on how to go faster through texts.

Utilitarian reading

The need for speed also increased through changes in cultural attitudes. With the spread of Enlightenment ideas throughout Europe, books and reading became vehicles for an individual's self-development. For the upcoming bourgeois, the authoritarian discipline from Church and State gave way to the notions of advancement and emancipation, although these came paired with the concept of utilitarian efficiency.

Chivalry novels were deemed as detrimental given their "uselessness" of subject matter. Picture: Amadis de Gaule, French edition of 1560, the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library at the University of Toronto.

These attitudes focused not only on being a useful member for society but on getting the best out of the new possibilities for social mobility. The act of reading became emancipatory, capable of changing the structures of public discourse, yet it also bore a responsibility as a tool for progress. Reading, it was felt, should be done for educating oneself and not idly.

Efficiency as a term and concept kept evolving. From the notion of maximising output while minimising input it morphed into maximising output through the elimination of waste, where time not doing something useful is seen as waste. This view has slowly permeated all of our lives. Food consumption, holidays, education, children's spare time, and even reading must be as efficient as possible. In a sense, reading for entertainment without any specific goal can be seen as a waste of time that could be better used. Consider for example the utilitarian justification for reading Don Quixote and other Classics.

Maximizing speed

In our contemporary societies, the activity of reading seems to be subdued to efficiency for various reasons beyond the over-availability of books. As the market ideology infuses every aspect of our life, a slow pace for doing things is seen as an outright waste of time. Efficiency plays a big role in our culture, seeking to use the resources at hand in the “smartest” way. However reducing resources for the sake of it might not always be the best thing to do. A hospital might endanger patients lives by overloading staff's schedules, or a reader might sacrifice pleasure and understanding by reducing the time he/she “spends” on a book.

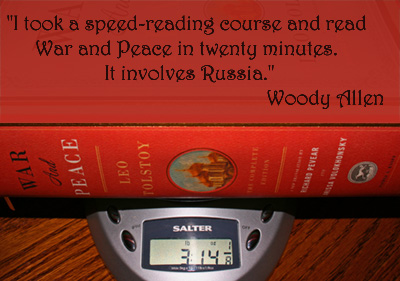

As a result, courses and techniques for speed reading (often in book format) have found their way to the market since the 20th century. It is worth noting that many of these methods are not based on science as there is a physical limit on how fast we can see and interpret texts. There is a difference between becoming a skilful reader through practice and applying techniques which compromise comprehension. In another version of the joke attributed to Allen, the columnist Earl Wilson says: “Jim Woelm from Minneapolis writes of a speed-reading course he took: it worked—I notice that I become confused much faster now.”

Newspaper ad for Evelyn's Wood Speer Reding Course, The North Texas Daily, February 9, 1971,

A technique often employed by readers which need to deal with a large amount of texts in a limited timespan is skimming. This consists on the quick scanning of a text looking for relevant information and is the type often employed by students when preparing for an exam or by researchers when they are evaluating many articles and books. The question arises on whether skimming a book or article can be called reading. In both cases the process of seeing and interpreting text takes place but the time for comprehension is definitely reduced in skimming.

TL;DR

The epitome of fast reading is “too long; didn't read”, which refers to only reading the headers of news items. There is considerable discussion on whether this should be called reading at all. To a certain extent it is, but assuming what the text says from the headers is not the same as reading it.

When people complain that many “do not read any more” they mostly refer to reading and understanding a whole text, which is seen as having implications for healthy public discussions. A person can read a text fast or slowly, can skim through it, or only read the header. All of these activities are reading albeit not always with full comprehension. These distinctions are important to consider, particularly when full textual transmission is deemed as one if not the main desirable outcome of reading.

---------

Further reading

There are several articles that take a critical look on speed reading, a few are:

- Sorry, But Speed Reading Won’t Help You Read More

- The Truth About Speed Reading

- Wait a minute... the thing is, you can't speed read

Quotes and Images

- Book flipping pages, picture by Nevit Dilmen (CC BY-SA 3.0)

- Bodin, Jean, 1530-1596. and Reynolds, Beatrice (trans). Method for the easy comprehension of history. Translated by Beatrice Reynolds. New York: Norton, 1969, c1945. http://hdl.handle.net/2027/heb...

- 1969 June 3, Richmond Times Dispatch, Show Time by Earl Wilson, Quote Page B19, Column 3, Richmond, Virginia.

- Evelyn Wood ad. Kelly, Terry. The North Texas Daily (Denton, Tex.), Vol. 54, No. 68, Ed. 1 Tuesday, February 9, 1971, newspaper, February 9, 1971; Denton, TX. (texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth326528/: accessed July 29, 2017), University of North Texas Libraries, The Portal to Texas History, texashistory.unt.edu; crediting UNT Libraries Special Collections.

© Andrea Reyes Elizondo and Leiden Arts in Society Blog, 2017. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Andrea Reyes Elizondo and Leiden Arts in Society Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

0 Comments