Medieval Women as Terrorists?

What connects medieval women to current discussion on violence and religion? This post looks into the projection of political ideas on historical figures.

Some time ago I went to The Hague to see the play Jeanne d’Arc, performed by the Nationale Toneel (National Theater). I wasn’t very well prepared, and was thus a bit surprised when the plot of the play differed strongly from the life of the historical Jeanne d’Arc that I know as a medievalist. The play began along familiar lines with Jeanne receiving divine visions, but later in the play Joan falls uncanonically in love with the English prince Lionel, and dies not at the stake but in battle.

These plot changes, as I learned from the programme booklet, were made by the German poet Friedrich Schiller, who wrote this play as Die Jungfrau von Orléans around 1800. His motifs for writing the play were political: he wanted to promote the idea of the German nation state, which did not yet exist at the time. His nationalism was fueled by the Napoleonic wars. Schiller called his Maid of Orléans a romantic tragedy.

In the twentieth century Schiller’s nationalistic approach has not always been looked upon favourably. Thus, it is an interesting choice of the Nationale Toneel to perform this play now, when nationalism is again seen as suspect. Although this production followed the script by Schiller, director Theu Boermans changed the political layer of the play by showing film images of twentieth- and twenty-first-century war and violence in between the scenes.

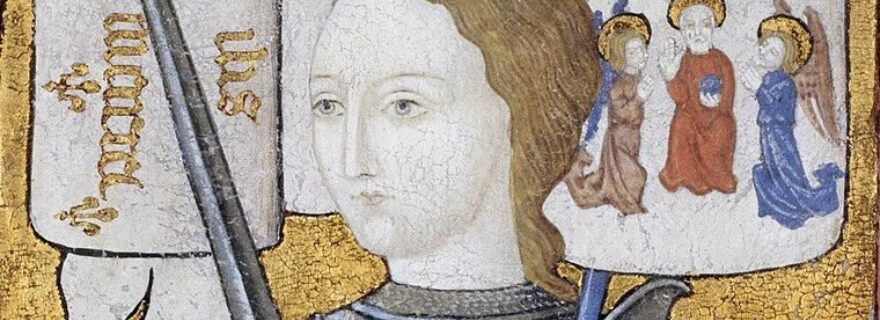

Johan of Arc - Archives nationales (France) - AE-II-2490 by Vinzez Sozvr Zovzanza ( Wikimedia Commons)

In an interview Theu Boermans explains the parallels he wants to draw between the medieval maiden of Orleans and current violent political conflicts. He paints Jeanne as a girl radicalized on the basis of her religion and asks the question: “what drives young people to extremist thoughts and deeds?” He compares Jeanne to Muslim girls traveling to Syria to become suicide terrorists, and to Tanja Nijmeijer, a Dutch woman who joined the Columbian guerilla movement FARC. In the play, Jeanne’s cutting of throats is reminiscent of IS beheading videos.

Thus, Boermans’ Joan of Arc is not the medieval woman we know from historical records, nor Schiller’s nationalist symbol. She is a radicalized visionary who uses violence in the name of God. It seems that Boermans tries to place terrorism in a wider historical context, presenting it not as a problem of Islam but as a problem of humanity. However, his choice for a medieval woman suggests that the problems with extremism of Christianity and the West are only in the past.

Marine Le Pen is often associated with Jeanne d’Arc, defending France against foreign people Creative Commons license

The second medieval woman who has recently been associated with terrorism is a less likely suspect: the mystic Hadewijch from the Low Countries. While Jeanne d’Arc was, at least, engaged with war and physical combat, Hadewijch certainly was not. As I noted in a previous post, we know almost nothing about her life; she was probably a beguine who wrote about her mystical experiences around the middle of the thirteenth century.

The link between this mystic and terrorism has been made by director Bruno Dumont (who more recently made a film about the childhood of Jeanne d'Arc), in the experimental film Hadewijch (2009). The story can be summarized as follows: Céline/Hadewijch is a girl who, at the beginning of the film, resides in a convent. Because of her extreme asceticism she is sent back to her rich family in Paris. She comes into contact with Nassir, an Islam teacher, and is attracted by his radical notions of following God. After travelling to the Middle East, they commit a bomb attack in Paris together. The confusing ending shows Céline/Hadewijch back in the convent, where the police comes for her. She wades into water but is pulled back by a handyman.

Trailer of the film Hadewijch

The intertextual relation with the mystic Hadewijch is not merely in the title; throughout the film various quotes from Hadewijch’s work can be found. Examples are Hadewijch’s assertions that “the sweetest thing about love is its violence” and that “to die for Love’s sake is to have lived enough”. These quotes imply that Céline already had destructive, violent tendencies befoe she met Nassir. Hadewijch’s ideal of the mystic as a servant or knight-errant of Minne (Love) is paralleled with Nassir’s notion of himself as a soldier for his faith. Moreover, Céline recites several lines from Hadewijch’s Poems in Stanzas to a sculpture of Christ, when she has returned to the convent at the end of the film:

Alas, Love, temper your mighty power

You have the days, and I the nights.

Why, when you force me to go out hunting for you,

Do you flee so far ahead of me?

You make me pay such a tribute,

I shudder that ever I was born a human being.

Dumont’s Hadewijch explores the connection between vehement desire for God’s love and the use of destructive violence in the name of one’s religion. While this is not exactly what we read in the work of the historical Hadewijch, the film of course does not claim historical accuracy and creates a new narrative. It is interesting however, that, like Jeanne d’Arc, Hadewijch is yet another medieval visionary woman becoming an embodiment of radical love for God and destructive violence in the present.

A more positive portrayal of the female mystic Hadewijch can be found in the opera Revelations, based on Hadeijwch’s Visions and performed in Antwerp last April. It claims to be an opera about spirituality, ecstasy, love, and the entanglement of cultures. This last element is explained by comparing Hadewijch to Mohamed El Bachiri, a Muslim from Brussels who lost his wife Loubna in the recent terrorist attack. His story, combined with fragments from his speeches and poems that he wrote, are published as A Jihad of Love and has become a bestseller in Belgium and in The Netherlands.

TEdx talk by Mohammed El Bachiri

There are indeed similarities between the ideas of El Bachiri and Hadewijch. Both stress the fact that love for God should coincide with love for fellow human beings – described by El Bachiri as vertical and horizontal love, respectively. Moreover, he explains that originally jihad means ‘effort’ or ‘striving’ – a striving against your own passions and a quest for knowledge and encounters with others. This seems a contradiction with Hadewijch’s most famous term ‘orewoet’: the vehement passion and desire for God. However, this understanding of jihad can be compared with Hadewijch’s quest to direct her desires to God instead of worldly matters, and her efforts to initiate and guide a group of friends or pupils in the mystical path.

Of course, El Bachiri and Hadewijch differ in many ways and should both be seen as reacting to the struggles of their own time. It is, however, refreshing that the opera Revelations invites a real engagement with the thoughts of the medieval mystic, instead of using her just as a projection screen for current political affairs. Opening up the dialogue between Hadewijch and El Bachiri can hopefully lead to a fruitful interreligious exchange, and the focus on the positive qualities of religion forms a welcome counterbalance to the critique on Islam, or religion in general, as inherently violent.

The play Jeanne d'Arc, the film Hadewijch, the opera Revelations and El Bachiri's Jihad of Love contribute to a discussion about religion and violence that is also held on a more theoretical level by authors such as Karen Armstrong. These creative exploration of the theme show the many ways in which history can play a role in current political discourses.

Further Reading

Marina Warner, Joan of Arc: The Image of Female Heroism (New York 1981).

For the text of Schiller’s play, see: Schiller's Jungfrau von Orleans (London 1998).

Hadewijch: The Complete Works, transl. by Columba Hart (New York 1980).

See also this graphic novel about the medieval mystics Hadewijch and Ibn ‘Arabi: Sjoerd-Jeroen Moenandar e.a., Zoet & Wreed: De Liefde van Hadewijch en Ibn ‘Arabi (Groningen 2010).

© Lieke Smits and Leiden Arts in Society Blog, 2017. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Lieke Smits and Leiden Arts in Society Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

2 Comments

Thank you for using my photo in your article! And what about the RAF-women (Meinhof, Ensslin, Mohnhaupt etc.)?

Kind regards, Blewbird

Thank you for using my photo in your article! And what about the RAF-women (Meinhof, Ensslin, Mohnhaupt etc.)?

Kind regards, Blewbird