After dark falls: the night as a space-time of migrant community building, reflection and resistance

Even though we mostly sleep through it, the night is an important space-time for different communities to get together, to remember and share experiences. As a PhD Candidate for the NITE project, Seger Kersbergen rediscovers the centrality of the night for Cape Verdeans in Rotterdam through music.

The city of Rotterdam is beautiful at night. You can enjoy a nocturnal walk along the Maas River, with views on the iconic Euromast tower, or catch a glimpse of the famous Erasmus bridge. But does everybody experience the night in the same way? As part of my fieldwork for the NITE (Night Spaces: Migration, Culture and Integration in Europe) project, I visited a multitude of night-time events organized particularly by Cape Verdean Rotterdammers. After a couple of these nights, unfortunately COVID got in the way. It is not a coincidence that in Rotterdam the Cape Verdeans are known (at least to insiders) for their nightlife endeavours – ranging from small scale traditional concerts to large club nights. To explain this, let me go back to where Cape Verdean nightlife in Rotterdam started.

Cape Verdean men started to arrive in Rotterdam since the fifties. Most of them came to find work in what was between 1962 and 2004 the largest port in the world, before Shanghai and Singapore outclassed the Dutch port city. Often, these ‘men’ were in fact still underage upon their arrival. Cape Verde was a colony of Portugal, only gaining independence on the fifth of July 1975. Many men looked to go abroad in the sixties, escaping hunger, unemployment and oppression. Some were seeking to escape military service in the Portuguese army, which was since January 1963 embroiled in a guerrilla war against independence fighters, led by revolutionary Amílcar Cabral. With some migrant pioneers established in Rotterdam, more Cape Verdeans started to arrive in the port city and a community started forming.

During my research period, in both personal interviews and archives, first generation Cape Verdeans share stories of comradery and mutual help in the diaspora. Those that arrived, without knowing where to go, were picked up and brought to a boarding house, of which many were in fact also established by Cape Verdean migrants. The first one was Hotel Delta, founded by Constantino Delgado in 1964. Delgado also helped newcomers find work at the ports, ensuring smooth sailing, so to say.

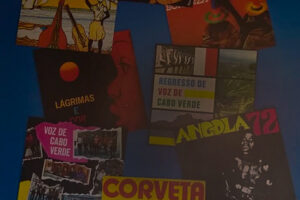

Resistance leader Amílcar Cabral was in close contact with another migrant pioneer, João Silva. Cabral was well aware of the importance of culture – and cultural expressions such as found in music and poetry – to stimulate awareness for the independence war and to generate a sense of Cape Verdeanness. Cabral wanted Silva to stimulate, spread and protect Cape Verdean culture in and from the diaspora, which Silva did by establishing the first Cape Verdean record label in the world, Morabeza Records. All of Morabeza’s music is digitized since 2016 and can be listened to here. The current curator of the label, Carlos Gonçalves, told me in an interview: 'The songs released by Morabeza often hid secret messages. A text about the love for your mother was actually about the love for your motherland. For example, Cape Verdeans were called upon via music to unite and fight for their country, without arousing the suspicion of the Portuguese.'

Sailors would covertly smuggle albums to the islands and spread throughout the diaspora worldwide as well. The production of music (and performances) occurred mainly at night. Before becoming professionals, the members of the Morabeza Records house band Voz de Cabo Verde (‘Voice of Cape Verde’), had to find work on land to make a living. The singer of the band, Bana, worked at the now iconic tea and tobacco factory De Van Nelle Fabriek, while multi-instrumentalist Frank Cavaquinho worked at the Heineken factory. Working shifts during the day, these artists needed the night to record and perform.

After some time, Voz de Cabo Verde started performing in the Latin-American nightclub La Bonanza. With the band in place, La Bonanza became an important night-time space of encounter for Cape Verdeans, enjoying familiar music, dancing, drinking, laughing, and flirting with Dutch ladies, of course. With the community growing, nightlife became an important instrument for generating belonging in the diaspora. Several Cape Verdean organizations in Rotterdam started to organize party nights as a means to get people together, to create a sense of ‘us’.

The Associação Caboverdiana (‘Cape Verdean Association’) was the first community organization in Rotterdam. It was founded by João Silva, among others. Under the radar, members of this organization were also involved in the independence struggle. In the context of nightlife, however, parties were consciously ‘designed’ to stimulate a Cape Verdean consciousness. Everything that was specifically Cape Verdean, such as music, drinks and food, was emphasized particularly, explains Gonçalves, while people simply had fun: 'The people who organized it did it consciously, but the people who went there [didn’t], it was giving people a good feeling that they could have some fun and be a Cape Verdean for a while.'

As social anthropologist Juliana Braz Dias (2008) states many Cape Verdeans think there is also an ‘inherent musicality’ to them. Rotterdam became the centre of Cape Verdean music production, with many record labels being established over time, attracting many artists, and creating booming nightlife. This tradition of Cape Verdean nightlife has survived for several generations, and even today you can find a large variety of events which are much worth visiting. After a long pause during the past two years I now see a boom in Cape Verdean events, witness to their resilience and spirit of community.

During the research period for the NITE project, which started in June 2019, all bars, restaurants and clubs closed suddenly when COVID hit the scene. Since I had initially planned to do physical night-time field work, this idea was to no purpose. I entered a conversation with cultural connoisseur Jorge Lizardo, who told me that many songs produced in Rotterdam also told stories about Rotterdam: about life in the city, going to sea, missing home, and even about nightlife adventures in the port city. It gave a new perspective for my research, and a great collaboration with Jorge. Hopefully in some months we can publish on this amazing musical archive of Rotterdam-Cape-Verdean connections. I will keep you posted!

Further reading

Dias, Juliana Braz. “Images of Emigration in Cape Verdean Music.” In Transnational Archipelago: Perspectives on Cape Verdean Migration and Diaspora, edited by Luís Batalha and Jørgen Carling, 173–88. Amsterdam University Press, 2008. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.....

Seger Kersbergen and Leiden Arts in Society Blog, 2022. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Seger Kersbergen and Leiden Arts in Society Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

0 Comments