Challenging Assumptions - Looking & Seeing

Archival research is extremely rewarding, whether you find documents that corroborate a hypothesis or that contradict it. Yet, balancing between contradicting sources can be tricky. In this post, Andrea talks about documents that challenged her preconceptions about the social fabric of New Spain.

Diving into the archives is time consuming but super fun and extremely rewarding, whether you find documents that corroborate your hypothesis or that contradict it. However, balancing between sources with contradicting "proofs" can be tricky and demands alertness.

Most historians are aware of the role that assumptions can play in our research. That is why we thoroughly assess our sources and the way we approach them. In this post, I talk about some findings in archives that challenged my preconceptions about the social fabric of New Spain.

Assumptions

We constantly make assumptions about the world and people that surround us; this is vital for our survival as it allows us to assess different situations quickly. Unfortunately, this can work against others, for example when concerns of black women giving birth are ignored by healthcare professionals. Sometimes this also works against us, for example when people vote for policies against their own wellbeing based on racist propaganda.

This is not only true in our everyday lives but also applies to us researchers. For example, for a long time it was thought that books which we now consider seminal must have also been popular and relevant in their own times. This bias steered research away from truly popular works, ignoring what people were actually reading. Thankfully, current research also focuses on books which were long considered as undeserving or irrelevant such as chapbooks.

Research on literacy

My research seeks to reconstruct the reading spaces, or reading possibilities, that were available at a specific period in a specific region. I am testing this approach in eighteenth-century New Spain by looking at different aspects necessary for reading to take place, and whether they were available and to whom. One of these aspects is literacy.

Measuring literacy is a tricky endeavor as the concept can mean different things at different periods. For example, nowadays literacy can include having basic digital skills next to being able to read and write. This gets much more complicated when you are studying people that have been dead for quite some centuries. For my period, I consider literacy as having the ability to read and write. A trace in archives that can attest to this are signatures in serial documents as an indication for basic literacy. However, even if you find signatures from people, does this mean they could read or that they read? This is one of the questions I seek to answer at the hand of other data such as the type of books published, their prices, and the cultural activities that “required” reading.

New Spain

Before we continue, you need to have some context of the ethnic and social fabric of New Spain. When the Spaniards arrived by chance in the Americas, there were more than 120 indigenous groups with very different languages, yet the Spaniards decided to call them all indios (indians). After the conquest, there were in the Spanish Americas also Spaniards, enslaved and freed blacks, as well as people with mixed ancestry (mestizos).

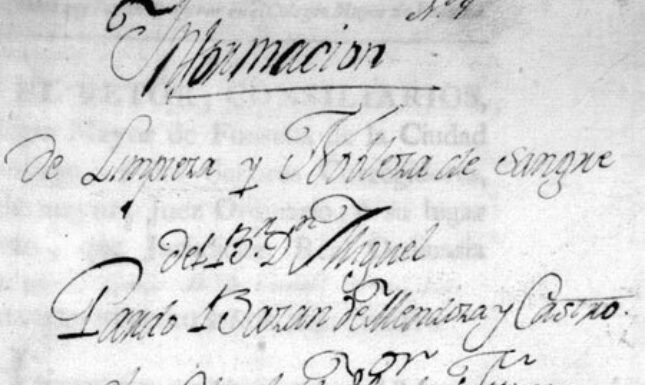

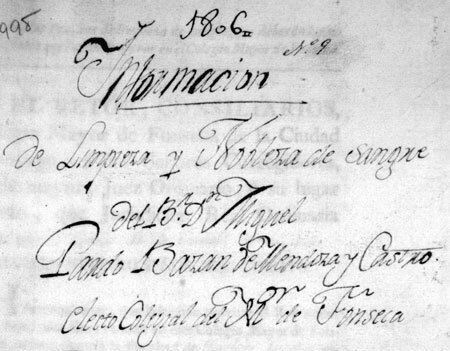

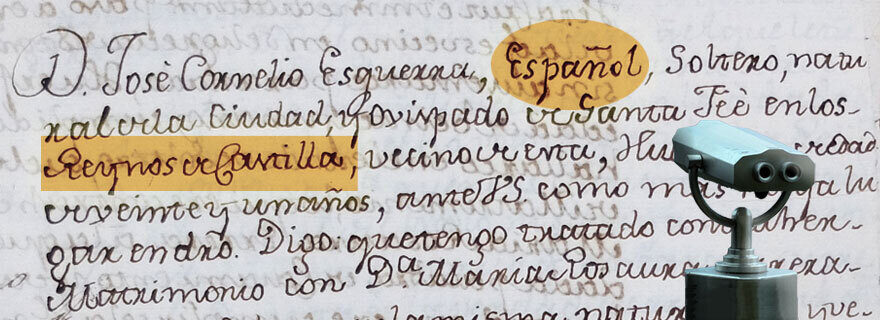

Being sorted into any of these groups was not based on very clear-cut criteria and followed perceptions rooted in the obsession with blood purity that engulfed Spain with the expulsion of Moors and Jews in the fifteenth century. In Spain, Church and State positions demanded a certificate of blood purity which guaranteed there was no Moorish or Jewish blood in a person’s lineage. Given that there was no objective way for asserting the “purity” of blood, people often relied on perceptions of others. For example, in the Americas one person could be of mixed or even indigenous ancestry, but because of their position and how others recognized them, they could be called español (Spaniard).

Very roughly the social scale was as follows, from bottom to top: blacks, mestizos, indigenous peoples, and Spaniards. Although at that time all Spaniards were called españoles, there could be a difference in access to power and status based on where they were born. For the colonial period in Spanish America we often divide them in peninsulares, those born in the “metropolis” (Spain), and criollos, those born in the colonies. For a long time, historians have assumed that most power laid with peninsulares, followed by elite criollos and noble indigenous peoples, with the rest down the ladder.

Back to literacy

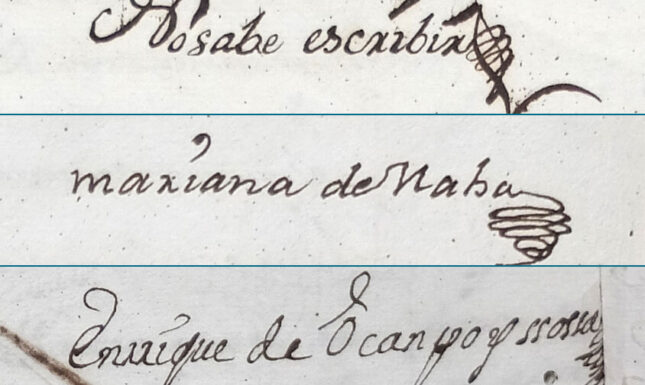

A way of measuring a very basic form of literacy is finding out whether people could sign documents. I have previously written about my work on the serial documents that I am using as sources. In these diligencias matrimoniales (marriage licenses), bride, groom, and witnesses would give testimony and be asked to sign. An interesting detail of these documents is that people who could not sign would rarely put a cross, rather the notary would state that “they cannot sign as they do not know how to write”. Most of the documents I have been working on seem to confirm my suspicions on who had access to at least a very basic form of literacy. Spaniards can sign more often, especially if they were born in Spain. Indigenous, blacks, mestizos, and women can rarely sign.

In a wedding document from 1778, all indigenous peoples that appear, including the bride, groom, a shoemaker, a baker, and a blacksmith, cannot sign after their testimonies (AGN, Matrimonios, Vol116, Exp002). In another document from 1704, the mestizos, enslaved blacks, and mulatos that partake in it cannot sign (AGN, Matrimonios, Vol 215, Exp 006). Nothing new here, we knew this, right? But then you start finding documents where women, and enslaved or indigenous peoples signed.

Other files seem to indicate the complete opposite of our assumptions. For example, a file from 1756 concerns the diligencia matrimonial of Joseph Marcelo Gómez and Mariana de Nava in Taxco (AGN Matrimonios, Vol 142, Exp040). Joseph was a 35 year old native to Grazalema in Cadiz (Spain), so one would assume that as a peninsular he would be able to sign. Wrong! He was a barber that did not know how to write. The bride was a 29 year old Spaniard born in New Spain, as a woman and criollo the assumption would be that she could not sign. Wrong again, she did sign. In the same file we find Enrique de Ocampo Sosa, a 31 year old mulato miner who acted as a witness. Did he sign? You bet, Enrique did sign.

Reality is complex and messy

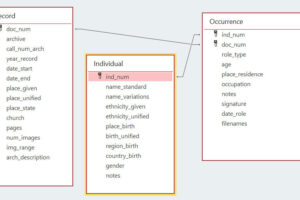

The above case illustrates the danger of false security that sources can give us. At the same time, we may ask, how common were these cases? A way to evaluate the incidence of the different signature occurrences is to do a systematic analysis of the sources. To this end, I am making an overview of a sample of documents to see how many people could sign and couple that to their ethnic background, occupation, gender, age, and place of birth. Although my preconceptions might make me more perceptive to cases where Spaniards could sign, this overview will help me to not lose sight of the total picture and ask myself: is this really the case?

This is not to say that we can understand the past (or the present) by putting information into a DB and running some queries. We definitely cannot and should not trust "data" blindly as the way to the truth. Reality is very complex and cannot be described in formulaic ways. Nevertheless, creating a DB can be a useful tool to test our hypothesis and if well designed, help us challenge our biases.

I would like to thank SHARP (https://www.sharpweb.org/main/) for their Research Development Grant for BIPOC Scholars 2021, which has allowed me to build this database as well as Mariana Solis López, who is transcribing together with me some of the 300 records.

© Andrea Reyes Elizonde and Leiden Arts in Society Blog, 2021. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Andrea Reyes Elizondo and Leiden Arts in Society Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

0 Comments