Fairy tales and cinema: a story of love and hate

Winter is coming as evenings are turning colder: the perfect time to rediscover fairy tales through their cinematic adaptations. But be aware that they could create a terrible debate…

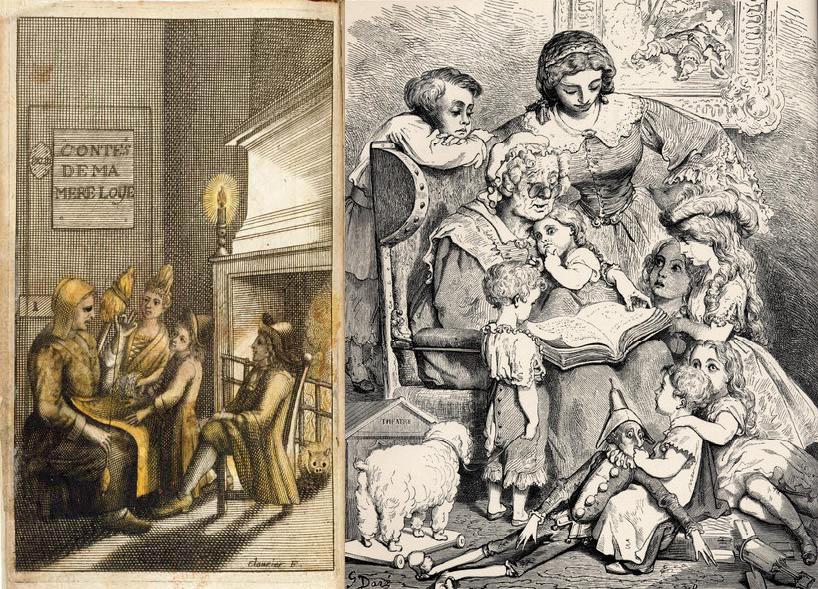

Once again, winter is coming: evenings turn colder every day and dinners outside are now an old memory. However, winter evenings are not so sad since they seem to be the perfect time to rediscover fairy tales: the traditional frontispieces themselves (the first illustration in a book, facing the title page), invite fairy tales’ very first readers to feel comfortable, surrounded by their family.

Left: original frontispiece of Charles Perrault’s tales, Histoires ou Contes du temps passé avec des moralitez par Charles Perrault. (Paris, Claude Barbin, 1697. (15,1 x 8,5 cm). Bibliothèque nationale de France)

Right: La Lecture des contes en famille. Gustave Doré’s frontispiece for Charles Perrault’s tales (Paris, Jules Hetzel, 1862. Gravure par Adolphe-François Pannemaker (33 x 27 cm). Bibliothèque nationale de France)

Fairy tales are traditional stories, told and retold many times before they were first written down as literature. They are intended to be widely shared and to evolve with every storyteller, reader or listener by an appropriation of the material. On the frontispieces, we can see that the fairy tales tradition already evolved between 1697 and 1862 since a book appears in the second one, in the very center of the picture, as a story-keeper. It’s also an invitation to look at the pictures: the painting on the wall is a real mise-en-abyme since it represents a first draft for a scene in the book, when Tom Thumb steals the Ogre’s boots.

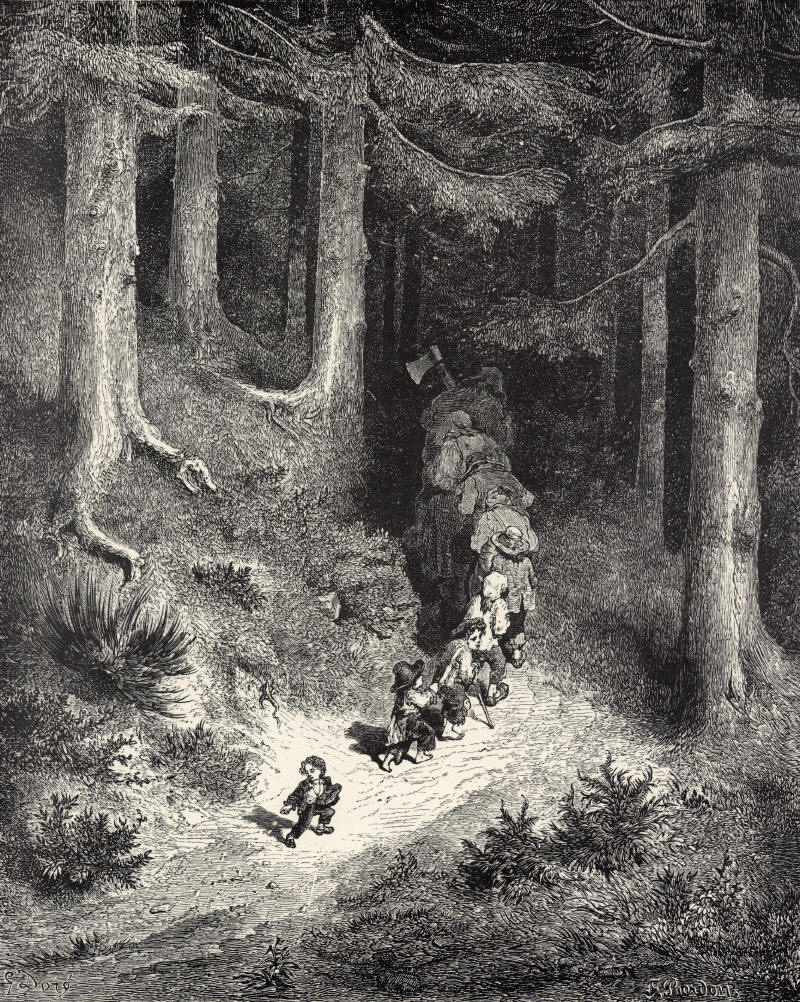

« Le Petit Poucet tirant les bottes de l’Ogre » for Charles Perrault’s tales (Paris, Jules Hetzel, 1862. Gravure par Adolphe-François Pannemaker (33 x 27 cm). Bibliothèque nationale de France)

There is a gap between these two traditions: books replace the teller’s memories, pictures supplant the listener’s imagination, and sight completes his or her hearing experience. Therefore, it’s not surprising that cinema, which is one of the most popular media, gets inspired by them. However, your fairy winter evening can turn into a nightmare if you suggest watching one of the many cinematic fairy tale adaptations, even more if you invite some literary purists among your friends while you dared to simply propose watching a movie. Prepare yourself to be harassed by them to know whether the one you choose respects the traditional story or not.

So what do people want when watching a fairy tale’s adaptation?

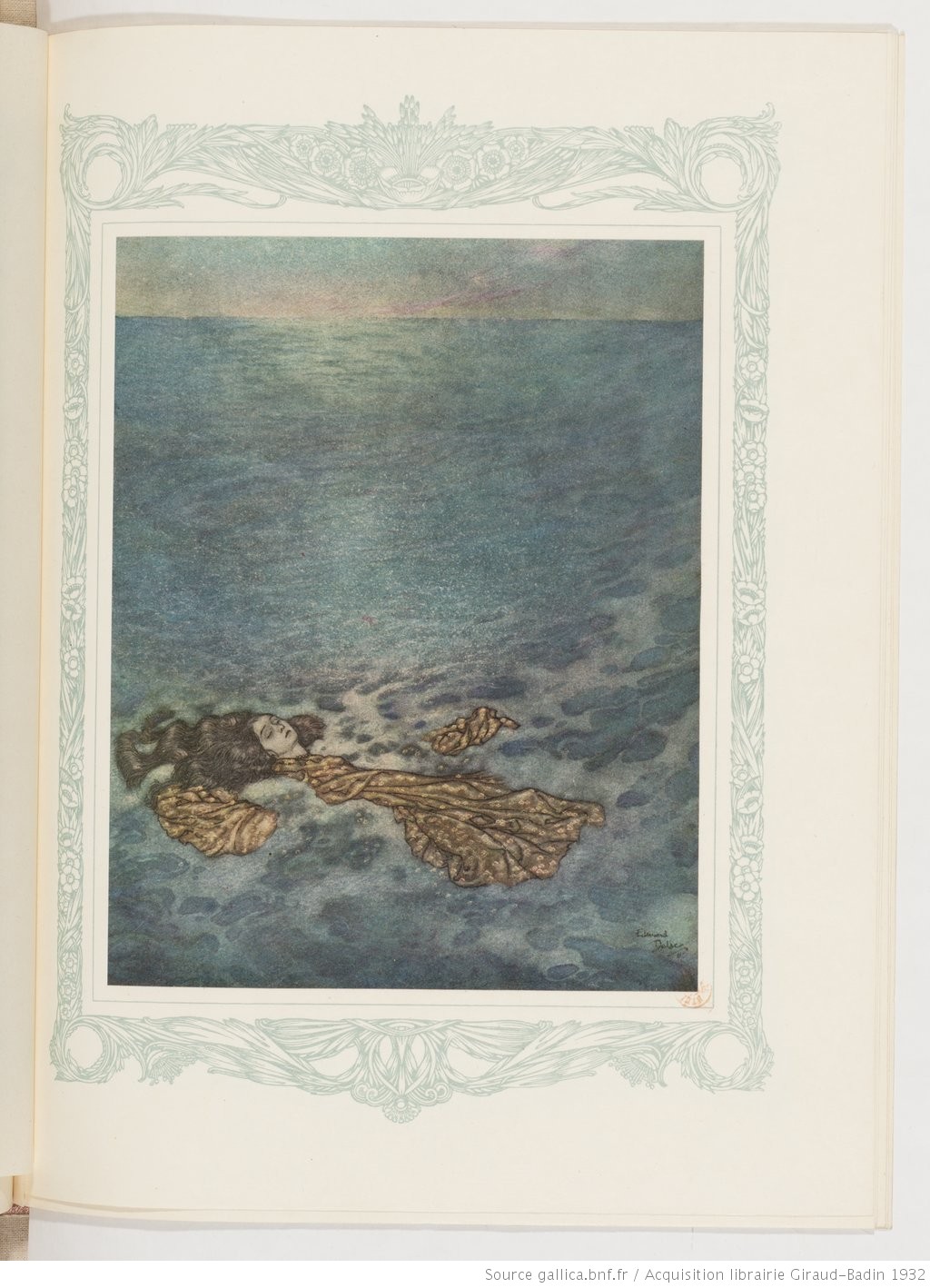

Adaptations are often criticized for not respecting the original tale: they are less cruel than the original story (like The Little Mermaid by John Musker and Ron Clements for Walt Disney Pictures in 1989), they skip passages, do not stick to the atmosphere of the tale, or are weirdly modernized…

An illustration of the Little Mermaid, showing a crueler ending than Disney’s one since the Little Mermaid turns into see foam after failing with the Prince, by Edmund Dulac, in La reine des neiges et quelques autres contes by Hans Christian Andersen (Paris, H. Piazza, 1911).

The examples are numerous: in The Red Riding Hood by Catherine Hardwicke (Appian Way Production, 2011) the viewer meets Valerie, a beautiful young woman wearing a red riding hood (mostly when something important happens in her life) who’s supposed to marry a wealthy man called Henry, although she’s in love with Peter. They plan to run away of course, but then Valerie’s sister is killed by a werewolf. After an investigation in the village, the werewolf turns out to be Valerie’s father, who finally contaminates Peter as a werewolf.

Snow White & the Huntsman (Rupert Sander for FilmEngine, Roth Films and Universal Pictures, 2012) which features a Snow White that has been training for war by the huntsman and dwarves replaced by an army, and Hansel & Gretel: Witch Hunters (Tommy Wirkola for Gary Sanchez Productions, Paramount Pictures, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer and MTV Films, 2013), whose title is enough for you to understand the disaster this film is, were released shortly after.

These three examples share a dark-and-gloomy atmosphere, teenage characters, action scenes and love stories, trying to attract Twilight’s audience by using the same codes, despite the promised tale.

An illustration of Hansel and Gretel meeting the Witch… No teenagers nor weapons… by Arthur Rackham, in The Fairy Tales of the Brothers Grimm. (London: Constable & Company Ltd, 1909)

On the contrary, adaptations can also be criticized for staying too close to the text, which would create a gap between the tale and our society and would compromise reception. Proponents of this theory often argue that social imaginary evolves, that today’s children are really different, and that adaptations can’t share the same values as fairy tales used to (especially concerning the place of women in society). In an article for the French version of the magazine Slate, Ursula Michel criticizes the movies that she considers the closest to the original story, explaining that today’s symbols are not the same as past ones. According to her, the woods that are often present in tales, seem less wild than they used to, when the Brothers Grimm made Hansel and Gretel lose themselves in there in 1812.

Illustration by Gustave Doré for Charles Perrault's « Le Petit Poucet » in Les Contes de Perrault (1867) with huge trees and dark woods for these little boys.

However, when criticizing, we have to keep in mind that changing the media means changing the public’s expectations, the codes of its reception and therefore changing the material itself. Watching cinema is different from reading a story, and reading a story (even out loud) is different from hearing it being told.

According to Christian Chelebourg in Les Fictions de jeunesse (Paris, Presses Universitaires de France, 2013), the most recent media in pop culture always use multiple senses to make immersion in the material more easy. 3D cinema, videogames which follow the player’s movements and augmented reality are some examples of this theory. Therefore, cinema can be one of the logical continuities of fairy tales evolution since it makes it possible to share a more complete atmosphere with pictures and sounds, leading to a fuller experience. This experience could be what people are looking for when watching a fairy tale as a movie instead of reading this fairy tale in a book. But on the other hand, fairy tales don’t usually give precise descriptions of the place, the time or the characters, who are “beautiful”, “poor” or “mean”. This gives a lot of space to the reader to imagine for instance “beauty” as he or she wants, ignoring the pictures if necessary, whereas cinema is obliged to fill these blanks with stereotypical representations which can offend its viewer and lead to criticism.

In my opinion, fairy tales are part of childhood memories: they are supposed to make us think, dream and fear while creating social cohesion. They are deeply linked to nostalgic feelings, which could explain that they are able to create passionate debates. The balance between modernization and respect for the original story, but also between leaving enough space to the viewer to dream and offering him or her a fuller experience is very fragile. However, sometimes it can be a real success. I think this is the case for Beauty and the Beast (Bill Condon, Walt Disney Pictures, 2017), a recent adaptation of Jeanne-Marie Leprince de Beaumont’s tale. In this adaptation, both Beauty’s sisters don’t exist anymore, whereas they are essential in the original story to prove that intelligence and beauty are less important in marriage than kindness (especially in arranged marriages, of course). It even makes the public feel that the Beauty falls in love with the Beast mostly for his intelligence. This choice is of course a modern one, considering that most people watching this movie will be able to choose their loved ones freely.

Walter Crane's 'Beauty and the Beast' (1874)

At the same time, Disney’s original songs comforted me in my childhood memory. The atmosphere of the movie echoes my childhood experience, but its modern choices satisfied my feminist convictions. For this reason, I’m truly convinced that cinema is able to give a second life to some ancient fairytales by modernizing them and interpreting them differently instead of only using them for commercial purpose.

References:

“Vie à nos rêves. Les contes de fees au cinema” by Alain Carou p. 270-277 in Il était une fois les contes de fees, 2001

Christian Chelebourg in Les Fictions de jeunesse, Paris, Presses Universitaires de France, 2013

© Céline Zaepffel and Leiden Arts in Society Blog, 2017. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Céline Zaepffel and Leiden Arts in Society Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

0 Comments