MOM 3: Blessed Be the Fruit: Why The Handmaid’s Tale’s Sexual Politics Are Not Medieval

23 to 31 March is the Dutch National Week of the Book. For this reason, the month March will be devoted to this year's theme ‘de moeder de vrouw’, as the Month of the Mother (MOM). This week: politics of sex, marriage and motherhood in The Handmaid's Tale.

Over the past two years many news outlets have commented on the relevance of Atwood’s 1984 novel The Handmaid’s Tale to today’s (post-2016 US elections) society. The New York Times even got the author herself to reflect on the connections between her story and the current political climate. The novel, now adapted for television, thematises the oppression of women’s bodily autonomy. The story takes place in an alternative world where the US is in crisis because fertility rates have dropped dramatically due to pollution. A reactionary Christian movement seizes power and founds the Republic of Gilead: a patriarchal society with a theocratic dictatorial regime and a strict class system. Highest in the hierarchy are the Commanders. If Commanders and their Wives are unable to conceive children, they are assigned a Handmaid. These Handmaids are ritually raped by their Commander each month and have the duty to produce children. If successful, they are forced to leave their babies behind and move on to another household. The red-and-white Handmaid uniform has become a powerful costume for protestors demanding, for example, the legalization of abortion, and demonstrating against the closing of a maternity hospital.

Women dressed as Handmaids demanding the legalization of abortion in Argentina (source) Creative Commons.

Besides pointing out parallels with our current society, people often compare Gilead, and especially its treatment of women, to a society that is quite distant from our own: the Western Middle Ages.[1] A piece on the book in the Washington Post, for example, claims that Gilead’s women “have been drop-kicked back to the Middle Ages”, while a blog article states that Gilead’s “government leverages sexual slavery by making use of a twisted moral justification – kind of like medieval handmaids”.

This association is not surprising. The book’s title is a reference to the medieval Canterbury Tales by Geoffrey Chaucer, containing stories with titles like ‘The Knight’s Tale’ and ‘The Prioress’s Tale’. Moreover, many aspects of Gilead have parallels in medieval culture: its religious laws, societal immobility, homophobia, misogyny, and praise of fertility – although all of these things are not exclusively medieval. Atwood herself has revealed that she has used solely events that have happened in history to construct her dystopian society, with a large role for seventeenth-century American Puritanism. However, when taking a closer look at Gilead’s religious ideas and sexual morals, we can only conclude that there are vast differences with medieval Christianity. In this post I will point out some of these differences, and argue that calling everything bad ‘medieval’ is unproductive.

Book cover (source) Creative Commons.

Polygamy

Gilead’s Handmaid system has connotations of non-consensual polygamy, concubinage, and sexual slavery – in all cases involving one man being married to or possessing several women. The system is legitimized with the Old Testament story of Jacob, Rachel, and Bilhah. Jacob had two wives, the sisters Leah and Rachel. While Leah gave birth to seven children, Rachel seemed unable to conceive. Therefore, she offered her handmaid Bilhah as a concubine to Jacob, allowing him to impregnate her and claiming the children as her own. In the Hebrew Bible, polygamy is not the norm but is allowed in some cases of necessity, e.g. for reproductive purposes. Jewish culture knew various internal and external laws, such as Roman prohibitions of polygamy, that restricted and regulated the practice, until it was completely prohibited in the eleventh century.

The New Testament does not continue the Hebrew Bible’s condonance of polygamy. As Paul proclaimed in 1 Corinthians 7,2: “let every man have his own wife, and let every woman have her own husband”. In the early Christian tradition, marriage was defined as a sacred bond between one man and one woman, and all forms of polygamy were considered as adultery. From the fourth century onwards canon law prohibited polygamy, and in the ninth century it became a capital crime. The necessity for such laws implies that polygamy did exist, but the practice was not state-condoned as in Gilead.

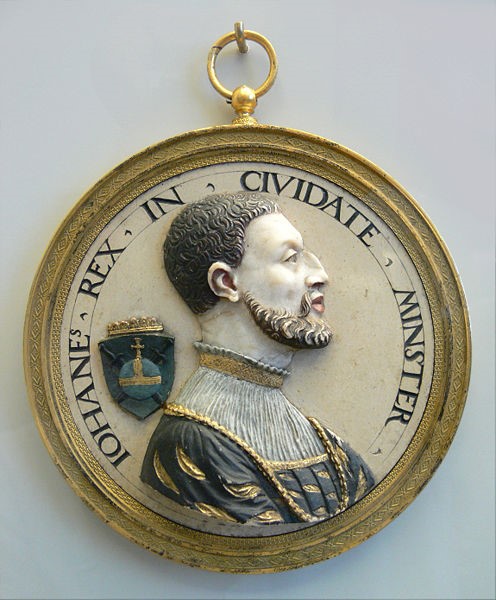

John of Leiden, King of the Anabaptists, c. 1535, Skulpturensammlung (inv. no. 820, from the Royal „Kunstkammer“ collection), Bode-Museum Berlin (source) Public Domain.

Gilead’s sexual morality is actually closer to some post-medieval protestant experiments with polygamy. Reformers reacted against Catholic laws on issues such as clerical celibacy, the sacramentality of marriage, and sexual restriction. A famous albeit non-representative case is that of John of Leiden, who proclaimed himself King of Münster in 1534. He founded a polygamous theocracy modelled on the Old Testament patriarchs. Unmarried women were forced to accept the first marriage proposal. This is not the only example of post-medieval Christian polygamy: in the United States Mormons used to condone polygamy in the past, and some fundamentalist groups still do.

Child Marriage

Another issue of sexual morality in Gilead is child marriage. The book describes arranged marriages with brides of only 14 years old, and in the TV series one of the characters marries a 15-year-old girl in a mass wedding ceremony. The couple is expected to consummate the marriage in order to conceive children. While in the popular view of the Middle Ages girls were forced to marry young, this idea is mainly based on the marriage practices of the aristocracy, where children were married off for political reasons. These child brides were usually not expected to consummate their marriage until they were older, since young pregnancies were a health risk. Laws did allow girls to marry from the age of 12 onward (for boys the minimum age was 14), but after 1300 the average age for women to get married for the first time, although varying according to period, region, and social class, was likely to be around 20 years.[2] Thus, while Gilead’s practice of child marriage does have parallels in medieval law and practice, it was not the norm.

Marriage ceremony from BL Royal 10 E IX, f. 195 (source) Public Domain.

Sexual Politics Based on a Literal Reading of the Bible

The way in which Gilead’s sexual politics stem from a fundamentally non-medieval reading of the Bible is apparent from a scene in the TV show in which the newly-wed girl Eden seeks advice on marital matters. The Commander’s Wife of her household argues that God approves of pleasure in sex within marriage by quoting from the opening of the Song of Songs in the Old Testament: “Let him kiss me with the kisses of his mouth: for thy love is better than wine”. Medieval exegetes did not link this sensual book to marriage or bodily love at all; it was interpreted as expressing the bond of love between God and either the Church or the human soul. The Song of Songs was connected with a religious lifestyle, where one could opt to marry Christ instead of a worldly spouse, and live as nun, beguine, recluse, lay sister, or even as abstinent in wedlock.

The scene in which The Song of Songs is quoted, in Season 2 Episode 5.

Protestants tend towards a more literal interpretation of the Bible. The Song of Songs is then interpreted as celebrating marriage and worldly love, as the Commander's Wife does. Similarly, we have already seen that Gilead interprets the Biblical story of Jacob, Rachel, and Bilhah literally as promoting polygamy, while medieval society did not. Following Biblical commandments to reproduce, the Republic of Gilead does not accept any form of abstinence from motherhood: nuns are persecuted and, when fertile, forced to become Handmaids.

Medieval or Modern?

Lately there has been an upward trend of framing everything that is perceived as violent, backwards or politically conservative as ‘medieval’ – especially things having to do with the Trump government. When Trump’s planned wall at the Mexican border was called medieval, he even appropriated the term, calling it a solution that worked then and works now. In many cases, things that are called medieval are actually not medieval, or they could just as well be ascribed to other time periods. Gilead is an example of this: some aspects of this society are medieval, although not exclusively, and some are very much not medieval, such as the Handmaid system.

Trump and medieval ideas | Drawn by Jake Tapper

There is another reason, besides factualness, to object to this manner of framing. Calling something medieval is an easy way to create a distance between the bad thing in question and our own society. As Eric Weiskott phrases it, “the ‘medieval’ label reinforces our overconfidence in ourselves and our modernity. [...] When we call something bad ‘medieval,’ it’s an attempt to purify the present by reassigning that objectionable thing to the distant past.” While those using the 'medieval' frame usually mean well and want to express their moral outrage over a phenomenon that should not exist in our time and culture (a valid reaction), it can prevent us from examining how the objectionable thing is part of our current society, which is a necessary condition for a constructive solution.

Further Reading

D.L. D'Avray, Medieval Marriage: Symbolism and Society (Oxford 2005).

Mark Goldfeder, ‘The Story of Jewish Polygamy,’ Columbia Journal of Gender and Law 26 (2014), pp. 234-315.

Daniel Lukes, ‘Neomedievalist Feminist Dystopia,’ Postmedieval 5 (2014), pp. 44–56.

Kim M. Phillips, Medieval Maidens: Young Women and Gender in England, 1270-1540 (Manchester 2003).

John Witte, jr, The Western Case for Monogamy Over Polygamy (New York 2015).

[1] Other frequent comparisons are American slavery and Muslim states. The handling of race in both the book and the television series has been heavily criticized. In the limited space of the post I will not go into this issue, but please read about it here and here.

[2] Phillips 2003, p. 37. In Italy, girls married younger.

© Lieke Smits and Leiden Arts in Society Blog, 2019. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Lieke Smits and Leiden Arts in Society Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

0 Comments