MOM 4: Every citizen needs a mother (or father) (II)

The Month of the Mother's (MOM) last blog: Not only men but women as well can exploit the parent motif in their political self-presentation. This week, we will look at the image of the female leader as mother of the people.

Do you become a better politician once you have had children? Is a woman who is also a mother per definition more qualified to lead other people than her childless peers? Since it is only for women to give birth, their motherhood is thought to be a unavoidable topic in discussing female leadership. I’m omitting for the moment the obvious practical and discriminatory issues, and would like to zoom in on the image of the political female leader who carries as an integral part of her identity her (potential) ‘motherhood’. History teaches us that this peculiar female feat can be used positively – strategically – in achieving political influence.

Mothers of society

Within a patriarchal civic society, traditionally it is motherhood which gains a woman respect. Put simply, women receive honour by delivering the men who form the political elite. Besides this, they were responsible for the organisation of the household, though they still needed to answer to the pater familiae, the head of the family. The matron fulfilled a special place in society: some Roman emperors would even choose to honour them by erecting temples in their name of their wives (Trajan, Antoninus), or stepmother (Hadrian). The Roman historians also tell tales of outstanding women, women who especially upheld the Roman values and claimed their rights or the rights of their own in the face of despotic or unlawful rulers. These beacons of modesty (for what else is the ultimate ‘female’ virtue?) could offer an example to every woman who was aware of her duty to her family and, by extension, the community. The writer Valerius Maximus (8.3.3) applauds Hortensia, whose father Hortensius was a genuine celebrity on the Forum. Hortensia demanded a remission of taxes before Mark Antony, the young Augustus and their wingman Lepidus in 42 B.C.. What’s more, she pleaded this case on behalf of the rank of the matrons, the by then mainly widowed – their husbands had been slaughtered by the aforementioned men – wives of the elite.[1] Unexpectedly, she won.

Hortensia, with the matrons standing behind her, speaks out against the Triumvirs. Provenance unknown. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Motherly qualities and feminine style

How would a Roman matron have addressed her fellow citizens? We should imagine she, the linchpin of an aristocratic family, appealed to the honourable status she possessed, and to the indignity of having to beg for mercy. As the person responsible for the harmonious condition and welfare of her family, she must also have called upon the humanity of her addressees, and their moral function within the community. Women may have been inferior to men in Roman law, but competent wives were in fact seen as authorities on many moral and social matters in and outside the family circle.

What has changed? Not so much, really, except for the fact that it is now legal for women to exercise power on a political level. (Yes, you reread that remark.) Research has shown that the female style in politics is associated with moral virtues such as honesty and modesty, and with a softer, more emotional approach. Family and marital status are usually highlighted in the portrayal of women politicians, both in their self-representation and by the media (Bystrom 2004). Ineke Sluiter, in her 2018 essay on Hillary Clinton’s self-presentation, has demonstrated that playing into one’s female qualities and experiences can be a very effective political strategy, as long as this type of self-portrayal is shown to be genuine and appropriate to the circumstances, i.e. the election or speech occasion.

Hillary Rodham Clinton on one of her election posters. Notable ‘female’ strengths are printed in a bigger font: ‘caring’, ‘willing’, ‘generous’ on the right; ‘faithful’ and ‘attentive’ on the left. Source: John Hain, Creative Commons

Is there a difference then, between a feminine and ‘matriarchal’ style? Perhaps there is, in the sense that feminine can easily turn into feminist, whereas a motherly attitude may appear less threatening to the male establishment. After all, most male politicians are intimately familiar with the concept of motherhood. While mothers are stereotyped for their reliability and caring nature, the female sex in general is traditionally seen as less dependable. We have mainly Aristotle and his theories about the ‘inferior species’ to thank for that.

This might be the reason why modern female leaders may be called ‘mummy’ without much trouble, although the image is not always appreciated: among others, Margaret Thatcher, Angela Merkel, and Theresa May have been nicknamed ‘Mummy’ by their rank and file. In spite of having this honorary title among her Tory followers, May became the target of an election riot in 2016 when one of her female competitors, Andrea Leadsom, deemed herself more suitable for the position of PM precisely because she was a mother, and May was not.

Playing mutti or mummy without actually being one

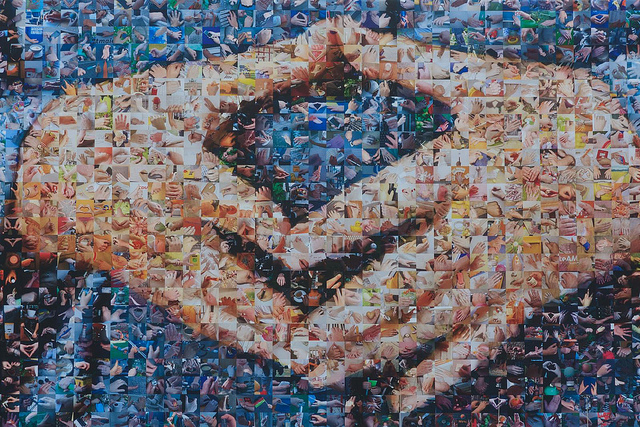

Both May and Merkel do not have children. Clearly, unlike in Roman society, in order to cultivate the mother image one nowadays does not need to be a mother except in the symbolical sense. With these modern examples we find ourselves in the realm of style, not of lived experience. We like to see our female leaders behaving (slightly) motherly, but we don’t like them to behave as if they are our mother. Women politicians are continuously walking a tightrope, finding the nuance between stern and modest, dominant and caring, professional and personal. Someone who has at last, after multiple makeovers, succeeded in doing this is Angela Merkel, Germany’s Chancellor or, simply, ‘Mutti’ (Mushaben 2017). According to the critics ‘Mutti’ is completely lacking in charisma but compensates for this by a characteristic consistency and trustworthiness. What expresses more calmness and authority than her two hands folded into the ‘Raute’?

The iconic image of the hands of Angela Merkel, on a huge CDU advertising poster fixed to Berlin Hauptbahnhof, as part of the 2013 election campaign. Picture: Thomas Dämmrich, Creative Commons.

The campaign video for the 2013 elections convincingly exploits the matriarchal strategy: we see Merkel, sitting on a sofa, speaking softly and reassuringly to the audience. As the final goal of her political programme, ‘Mutti’ Merkel – the camera zooming in on her eyes – confirms that her Germany is a country where “we can offer the best chances to our children”. Her last appeal is to harmony: ‘Gemeinsam schaffen wir das’. It doesn’t matter that Merkel in reality is childless. She has all the appearance of an elder authority who knows how to harmonise and unite others, and who is aware she has a model function. We would expect nothing less from any parental figure.

Further reading

D. Bystrom, ‘Women as Political Communication Sources and Audiences’, in L.L. Kaid (ed.), Handbook of Political Communication Research (Mahwah, NJ/London: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 2004).

M. Laterveer (ed.), Wolf. Dertien Essays over de Vrouw (Amsterdam/Antwerpen: Atlas Contact, 2019).

M.R. Lefkowitz & M. B. Fant (eds.), Women’s Life in Greece and Rome (London: Duckworth, 1982).

J. M. Mushaben, Becoming Madam Chancellor: Angela Merkel and the Berlin Republic (Cambridge/New York: CUP, 2017).

I. Sluiter, ‘Een betrouwbare vrouw’, in J. de Jong, O. van Marion & A. Rademaker (eds.), Vertrouw Mij. Manipulaties van imago (Amsterdam: AUP, 2018).

[1] A dramatic version of Hortensia’s speech is found with the Roman historian Appian, book 4.32-34.

© Leanne Jansen and Leiden Arts in Society Blog, 2019. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Leanne Jansen and Leiden Arts in Society Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

0 Comments