Personae as a Historical Research Method

The writing of history is a continuous process. Speculative methods like personae can aid us in enriching our understanding of history with the stories of the peoples without history, and allow us to ask ourselves: “how was it then”?

For long historians have focused on the lives of important people: kings, philosophers, generals, and scholars. Among all the stories that have been written about these ‘big fish’ of history we find almost no sprat: women, minoritized, and enslaved peoples. The focus on the big fish is understandable; besides having played a role in watershed moments they left plenty of traces in documents, properties, jewelry, and sometimes even their own writings. In contrast, the sprat rarely left those traces. Many of them could not write, and their possessions have often been lost. Nevertheless, there are ways to let their voices speak, for example, through speculative methods like personae.

In the novel The book of Collateral Damage by Sinan Antoon, the main character—who is an academic himself—writes the following: “There are people who write in order to change the present or the future, whereas I dream of changing the past.” History is often seen by the general public as a narration of events “as they happened.” However, the writing of history is never truly complete. There are people and events that are highlighted, while others have not been included.

Looking for the sprat

Luckily there are more and more historians who seek to also consider the lives and experiences of regular people, and what their stories can tell us about the history that we write. In The Cheese and the Worms, Carlo Ginzburg rescued from the archives of the Inquisition the story of Menocchio, and thanks to this “unimportant” man he enriched our understanding of the flows of knowledge between low and high culture in the sixteenth century.

In this case there was plenty of documentation in the archives. But what to do when there is little information?

Several scholars have focused on this question. Sadiya Hartman has sought to give a voice to the enslaved black women who were but a footnote in archives. Caroline Dodds-Pennock showed how Indigenous peoples from the American continent were present in Europe since the sixteenth century. And Suze Zijlstra tracked her Euro-Asian foremothers from the Dutch Indies. Each of these historians has used different approaches and methods, but the basis was always the archive, as scant as the traces might be. Other scholars make use of speculative methods. Ruha Benjamin wrote a story that takes place in the near future where Black liberation has been accomplished, to explore the possibilities of the present and ask what is necessary to achieve such a future. Beth Driscoll and Claire Squires have created personae to research the dynamics of the Frankfurter Buchmesse, an approach that has inspired me to explore the possibilities that this speculative method can offer to historical research.

Reading and non-reading sprat

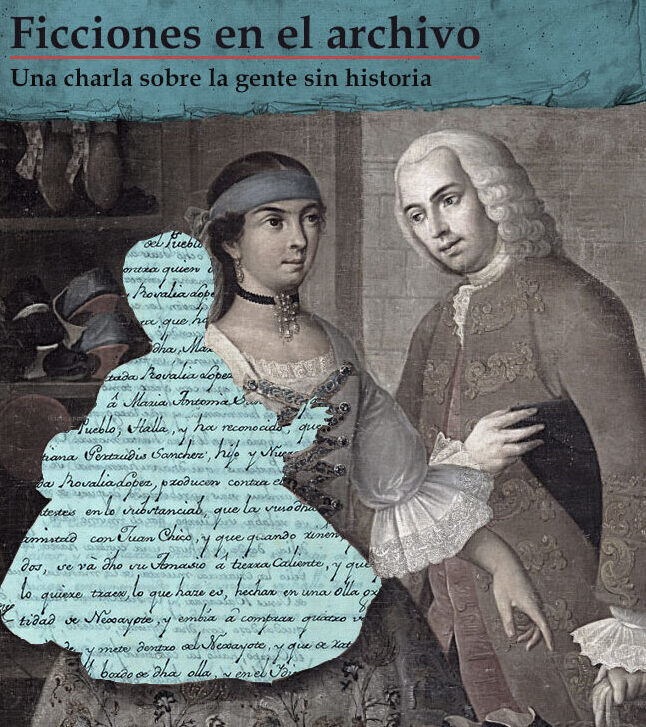

As a book historian I am aware that our discipline has also focused for a long time on the big fish: those who left large book collections or who were printers and writers themselves. However, as in other history disciplines, the focus has expanded to the sprat. For example, by looking at what women and other marginalised groups read. For my research I am seeking to reconstruct the reading spaces, the reading possibilities available in eighteenth-century New Spain (colonial Mexico). To reconstruct these I do not only focus on why and for which activities people read; I also focus on how those who could or did not read carried out similar activities, such as spiritual and healing practices, entertainment, devotions, festivals, etc. Through this approach I seek to situate the activity of reading in the larger cultural and multimedia environment.

Finding the daily and extraordinary activities of regular people in the archives can be challenging. Sources such as court cases can offer us a glimpse of these, although we must be conscious of the purpose with which such documents were prepared. For my research, the Inquisition archives are an extremely rich source: through the lines we find traces of conflicts among regular people and glimpses of their daily lives. As all historical documents they are quite messy: oftentimes there are various testimonies per person, some pages are missing, and the “story” is never told in chronological order. After reading several of these types of documents, I believed I had a good idea of the lives of those involved in these cases. Then came book historians Driscoll and Squires inviting me to create a persona for a roundtable discussion for the SHARP 2023 conference.

Personae

The invitation was to create a fictional persona based on my own research. This may sound like a horrific disregard of the principles of archival research (do not make stuff up), however, the method is based on speculative research practices that can help us understand historical periods in an embodied manner. Although the process involves some playfulness, a persona is based on the knowledge that the historian has. Rather than making things up, it is a merger of people and events from the archives.

The creation of a persona demands time and letting go of a rigid handling of historical documents. The result can be written down, or even better, performed in one’s living room or before an audience. For researchers without theatrical inclinations the latter might sound distressing; however, it is an excellent form to reflect on our periods and share them with a larger audience.

I have performed my personae in a couple of public lectures in Mexico, and in academic settings in the Netherlands and the US. The personae offered space to provide a different perspective on the colonial period of Mexico and generated miscellaneous questions from the audience. In the public lectures people were surprised and perhaps even disappointed that the personae had not been executed; the discussion also arose on why in Mexico there is such little attention to this period in our educational system. In the academic settings, several colleagues shared similar methods and some wondered how they could apply these to their own research. Nevertheless, for others it remained a nice idea that they could never apply as it felt “unserious.”

Rosalía and Manuela

My two personae for eighteenth-century New Spain are Rosalía López and Manuela Josepha Galizia, both strongly based on two historical women. Rosalía is a woman from the countryside who makes and sells bacon, is married but has a lover, uses a talisman to call for her lover, knows healing remedies from herbs and plants, wants to be present in every gathering, and has been accused of killing a woman giving birth through witchcraft. Manuela Josepha is a curandera (healer) from Mexico City who has cured many people with ointments and tortillas made with a special bouillon. She has cured a woman who was nauseous for years, a man who had turned black because of his illness, and a young woman with a lump on her belly. Manuela had once seen the Virgin Mary in a dream, and her statue of Saint Cajetan had miraculously sweated; she was accused of claiming to be able to perform miracles.

For each persona I perform a narrative text and make use of props: a hummingbird talisman for Rosalía and handmade tortillas for Manuela Josepha. Learning the texts and performing the personae offered me a grounded and bodily way of knowing. The personae allowed me to understand daily lives and reflect on the question of whether reading had a role and use for the spiritual and cultural activities of many people.

Speculative methods can enable us to see events and environments in a different light, enriching our understanding of past periods. While texts played an important role in the lives of people during the period that I study, many never read or wrote. In the archives I have studied I have found merchants who could not write. How was that possible? As a person for whom literacy is a matter of fact, it feels impossible to imagine merchants could carry on their trade without knowing how to write. The speculative method of personae allowed me to explore cultural activities in a richer manner than by only reading documents in the archive. Through these experiences I can better situate the place of reading in the cultural and media landscape of eighteenth-century New Spain, an activity that was not carried out by everybody but which was also not reserved for the elite.

This post has been previously published in Dutch in Over de Muur.

Literature

Sinan Antoon, The Book of Collateral Damage (New Haven & London: Yale University Press, 2019).

Ruha Benjamin, ‘Racial Fictions, Biological Facts: Expanding the Sociological Imagination through Speculative Methods,’ Catalyst: Feminism, Theory, Technoscience 2(2) (2016): 1-28. https://doi.org/10.28968/cftt.v2i2.28798

Beth Driscoll en Claire Squires, ‘The Frankfurt Book Fair and its Cupboards,’ Public Books (10 December 2023). https://www.publicbooks.org/the-frankfurt-book-fair-and-its-cupboards/

Beth Driscoll en Claire Squires. ‘THE ULLAPOOLISM MANIFESTO,’ ASAP/J (2021). https://asapjournal.com/feature/the-ullapoolism-manifesto-beth-driscoll-and-claire-squires/.

Caroline Dodds Pennock, On Savage Shores. How Indigenous Americans Discovered Europe (London: Weidenfeld and Nicholson, 2022).

Carlo Ginzburg, The Cheese and the Worms.The Cosmos of a Sixteenth-Century Miller, translated by John and Anne C. Tedeschi (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2013).

Saidiya Hartman, ‘Venus in Two Acts,’ Small Axe 12(2) (2008): 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1215/-12-2-1

Suze Zijlstra, De voormoeders. Een verborgen Nederlandse-Indische familiegeschiedenis (Amsterdam: Ambo|Anthos, 2022).

© Andrea Reyes Elizonde and Leiden Arts in Society Blog, 2025. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Andrea Reyes Elizondo and Leiden Arts in Society Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

0 Comments