Radioactive Felines

Did you ever wonder what cats have to do with radioactive waste? Well, probably not. But hang on. In this blog post I will show you some curious web artefacts that certainly will.

During the Easter holidays, my cat-infatuated sister-in-law excitedly told me about ‘Stand Still, Stay Silent,’ a beautifully illustrated web comic that was created by the Finnish-Swedish writer and artist Minna Sundberg. The comic is set in a post-apocalyptic future, when most mammals on Earth have succumbed to a mysterious, infectious disease. Those who survived are living in Iceland and in small settlements scattered over the Nordic countries of Norway, Sweden, Denmark and Finland. Outside these settlements, the ‘silent world’ begins, a world full of terrifying trolls, giants and monsters that a motely group of academics and military officers sets out to explore after almost a century of isolation.

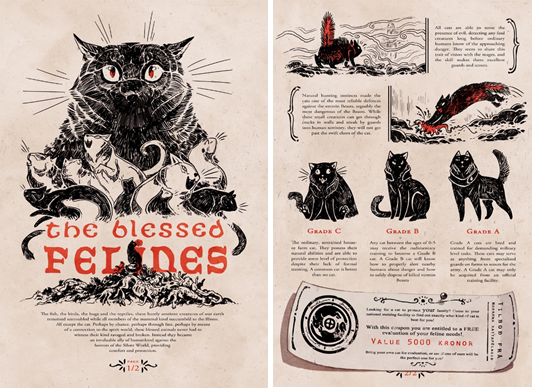

‘Stand Still, Stay Silent’ is basically about the adventures that this underfinanced and unqualified group of humans experience in the wasteland that is the silent world; and Sundberg’s graphical talent alone makes it certainly worth following them on their journey. But the main reason why my sister-in-law was so enthusiastic about this comic, is the prominent role of cats in it: due to their exceptional ability to detect evil long before humans sense the danger, cats figure in the story as guards and scouts, living detectors of malicious creatures so to speak. These ‘blessed felines’ are therefore indispensable companions for humans, especially when trained:

‘The Blessed Felines’ by Minna Sundberg

When I heard about the comic, I could not help but drawing connections to my research into marking strategies for nuclear waste sites that I was doing at the time. Because, as unlikely as it may appear to the uninformed reader, there is a weird link between cats and nuclear waste that is not that far off Sundberg’s post-apocalyptic fiction.

Don’t change color, kitty

‘Don't change color, kitty.

Keep your color, kitty.

Stay that midnight black.

The radiation that the change implies

can kill, and that's a fact.

The radiation, whatever that is,

is something we don't want,

'cause it withers our crops

and it burns our skin

and it turns our livestock gaunt.’

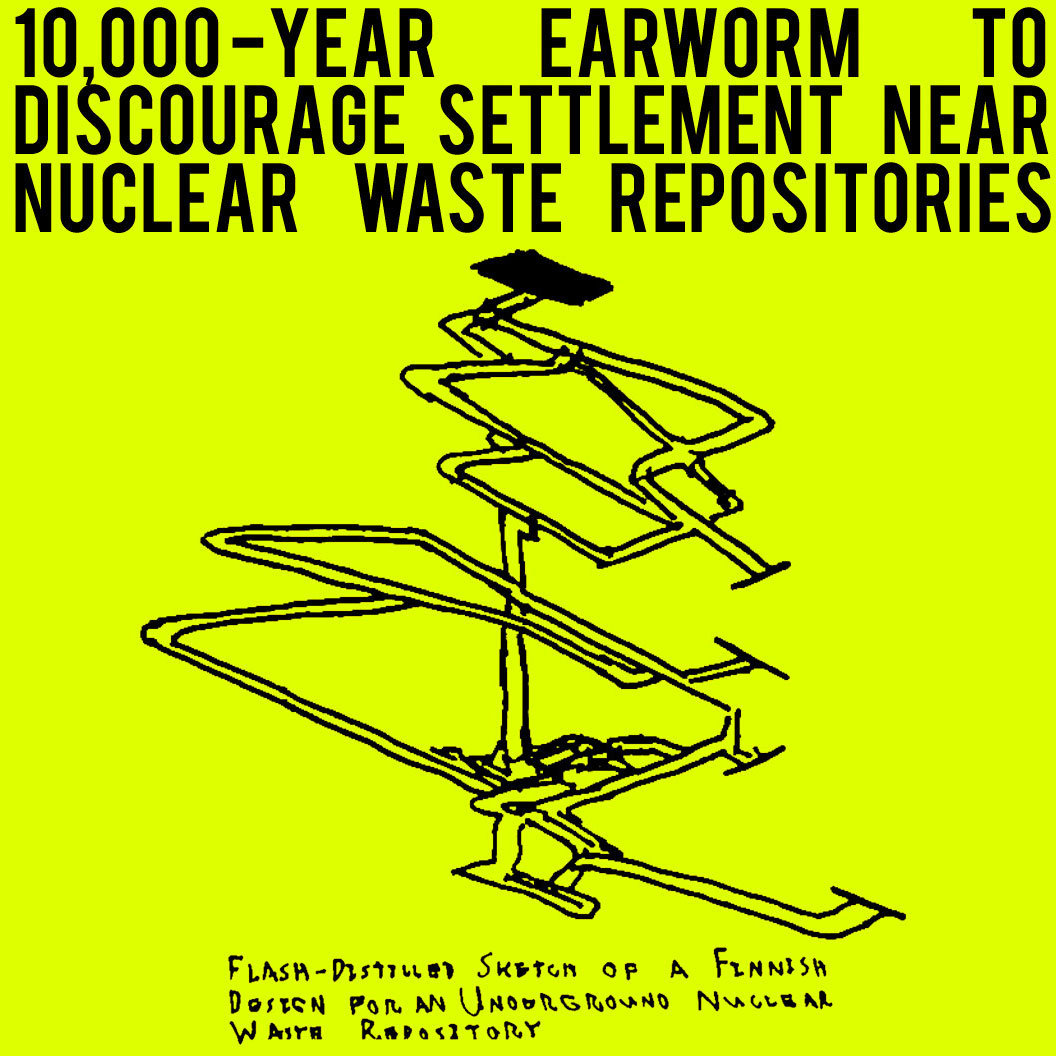

This is a fragment of the lyrics of a “10,000-Year Earworm to Discourage Settlement Near Nuclear Waste Repositories” that was written in 2014 by the American singer and songwriter Chad R. Matheny, professionally known as Emperor X (if you are not afraid of earworms, you can listen to the song here). They come with a simple, repetitive tune that, once heard, is hard to shake off. The bold aim of this earworm is, as the title states, to “discourage settlement near nuclear waste repositories” for the next 10,000 years.

Cover of the 10,000-Year Earworm, Emperor X

It may sound absurd, but this song is part of a strategy to prevent future humans from unintentionally intruding on radioactive waste isolation systems, more commonly known as deep geological repositories, like the soon to be completed Onkalo spent nuclear fuel repository on the west coast of Finland or the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant (WIPP) in New Mexico. And cats, obviously, play a prominent role in it.

Ray Cats

The idea of color-changing cats that the song utilizes stems from the French writer Françoise Bastide und the Italian semiologist Paolo Fabbri and was part of a serious proposal on how to communicate the danger of radioactive waste 10,000 years into the future. It was published in a 1984 special issue of the German Journal of Semiotics (Zeitschrift für Semiotik). The gist of Bastide and Fabbri’s proposal looks very much alike Sundberg’s ‘blessed felines’: what they basically suggest is to turn cats into living detectors that warn future generations against the dangers of leaking radioactive waste repositories. The ability to detect this man-made evil, however, would not be a natural trait all cats possess and could be developed by training as in Sundberg’s story, but is restricted to a group of genetically modified felines that would change color in the presence of radiation. Moreover, to carry the meaning of this trait from generation to generation, Bastide and Fabbri suggest to wrap their ‘ray cats’ in a corpus of spontaneously generated idioms, tales, narratives or myths that ideally reproduced over time like the tales of ancient gods.

Stickers and T-Shirts with the Ray Cat-logo, 99 percent invisible

A model to survive in an emerging toxic world?

Perhaps because the proposal was bold and published in German, the ray cats, like most other proposals in that 1984 issue, initially did not gain much traction and were basically forgotten for almost 30 years. For that reason, I found it even more astonishing to accidentally learn about these ray cats through a song that was recorded in 2014. In fact, when I dug deeper into the issue, I found that there is a growing crowd of people actively working on the realization of Bastide and Fabbri’s idea.

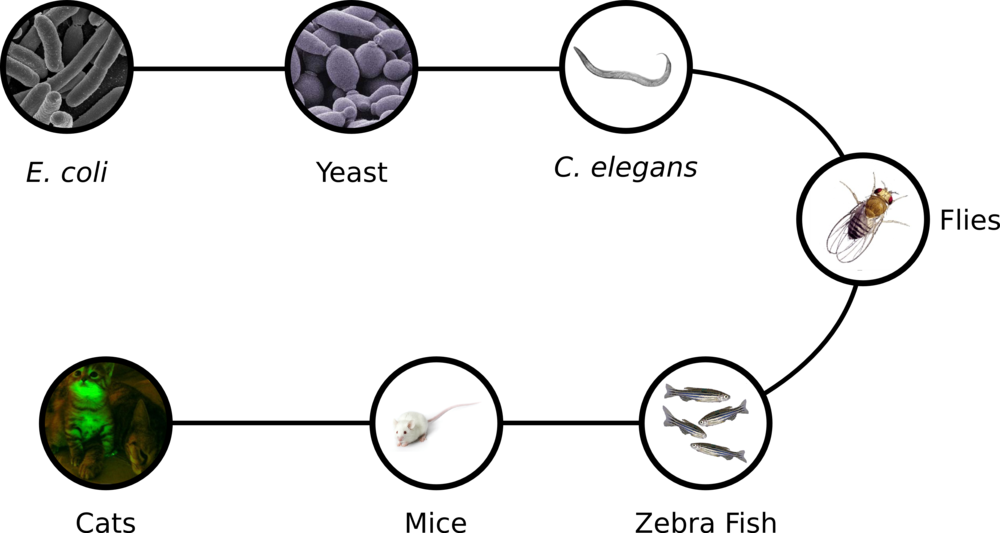

“The Ray Cat Solution”, short film by Benjamin Huguet.

It all started in 2013, when a New York journalist in search of a story by chance came across an English summary of the proposal and included it in a podcast on nuclear semiotics for the online platform 99% Invisible. Since then, the idea to use genetically modified cats as living radiation detectors has taken on a life of its own. Not only did major media outlets like The Guardian or Australia’s Business Insider took an interest in the topic, you can now purchase stickers and T-shirts with different ray cat designs, or watch the short film The Ray Cat Solution, directed by Benjamin Huguet. But most astoundingly, an independent laboratory in Montreal that goes under the name brico.bio has actually taken on the task to engineer animals that would visually respond to environmental pollutants and dangerous substances like radiation, mercury or carbon monoxide, working all their way up from bacteria to cats. Legal questions aside (is it even possible under existing law to genetically modify cats like this?), it is of course highly questionable if such an undertaking will ever succeed from a bio-technical, but also ethical point of view.

Brico.bio’s scheme to genetically engineer a ‘ray cat’, Bricobio

I should note therefore, that Brico.bio is not just a biology lab, but understands itself as an experimental platform for artists, designers, scientists and anybody who is interested to discuss strategies to survive in a toxic world. Bastide and Fabbri’s ray cats are surely not the most convincing solution to the problem of an irradiated world, but they appear to be a fruitful starting point to experiment with ideas and technologies to navigate the emerging complexity of a less biodiverse and more toxic world. And who knows, perhaps not long from now, humans will find themselves in a Sundbergian scenario, fighting (if not trolls and giants) mysterious diseases caused by leakages of the radioactive waste we’ve left behind? A ray cat would certainly come in handy then.

© Anna Volkmar and Leiden Arts in Society Blog, 2018. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Anna Volkmar and Leiden Arts in Society Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

0 Comments