Self-Isolation and Thucyd-…

It may seem attractive to turn to past medical practices and epidemics to see what they can teach us about the corona crisis, but Glyn has doubts about the usefulness of this approach. He would rather share some struggles of self-isolation as a single, non-teaching PhD candidate.

As a student of ancient medicine, I sometimes almost wish the physicians I work on would have practiced some more social distancing. The Hippocratics — the authors of the Greek medical treatises collected in the Hippocratic Corpus — were prone to touch, taste, and smell what came out of their patient’s bodies in order to properly diagnose diseases. For example, my favourite maxim from book 6 of the Epidemics (6.5.12) confidently states that earwax, when sweet, is a sign of death in the patient, while bitter earwax indicates a more positive outcome. Getting up close and personal with your patient means running the risk of infection yourself – this is true now during the current corona crisis, but was especially so in a time without face masks and disinfectants.

Interestingly, the concept of contagion seems to have been unknown to the Hippocratics, or at the very least, they make no mention of it, to my knowledge. It simply does not fit their model of a body governed by fluids, and oppositions such as hot and cold, dry and wet. In this model, where imbalance means illness, disease becomes a rather individual affair, a disturbance in a single body. Certainly, particular groups could be more prone to some diseases than others, but this is often due to their bodily constitution or as a result of seasonal winds and the weather: a disease could not simply spread from one body to another. The Greek historiographer Thucydides, on the other hand, does seem to have had at least a rudimentary concept of contagion in mind while writing his account of Athens during the great plague of the fifth century BCE.

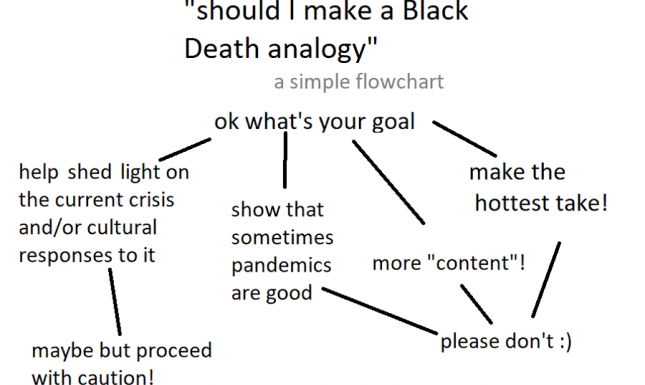

Comparing the highly contagious corona virus, spreading in no time over vast parts of the world, to ancient medical writings throws into relief some aspects of Hippocratic pathology as mentioned above — and, more importantly, emphasizes once again how thankful we should be towards our medical staff and caretakers for putting themselves at risk, all for our sakes — but not much beyond that. Perhaps, it is best to eschew comparisons to historical epidemics and medical practices altogether, or at the very least to follow this handy flowchart shared by a medievalist colleague, which I think works for ancient medicine as well.

One gets the faint impression that many medievalists are rather annoyed by the gratuitous comparisons of our modern health crisis to the plague sweeping through large parts of the world in the fourteenth century (and beyond) that pop up on the internet. And rightfully so, as they mostly do not add much to our knowledge of either the current situation or the plague, all the while sacrificing historical accuracy. As a classicist, I share this sentiment, although in my case the annoyance is aimed at Corona-and-the-Plague-of-Athens articles (that said, an insightful one can be found here). As it turns out, what we can ‘learn from’ the Athenian plague and its aftermath as told by Thucydides often consists of the warning that there will be great consequences for the economy and social life in the wake of a large scale epidemic — things we could have also learned by simply reading the news.

All of this crosses my mind working at the kitchen table in necessary self-isolation, which, admittedly, hits me harder than I initially thought it would have. Therefore, rather than adding to the list of gratuitous historical comparisons, I would like to dedicate the latter half of this post to some thoughts on the self-isolation of a PhD student. Let me immediately say that I am well aware of my privileged position here: work on my PhD thesis can be done from home, my monthly payments are in no way at risk, and I am healthy. Furthermore, I live alone, which means I do not have to face the difficult task of combining working from home with caring for (young) children, as many parents do.

Yet, living by yourself comes with it its own challenges. For one, self-isolation sometimes feels very isolated, a matter for which there recently has been some more attention in the news. Even without children buzzing around me, I find it difficult to properly concentrate on my work: besides the flurry of disconcerting news messages, I am also trying to wrap my head around the fact that my tiny apartment (home) and my office (work) are all of a sudden the same space, and I find myself getting easily distracted. This comes with worries, and sometimes even feelings of guilt, about diminished productivity, even though working on a PhD thesis means that productivity is sometimes hard to measure when you’re not writing, anyway.

We have all read the tips for working from home — get up on time, dress for work, stick to your usual rhythm, etc. — but these are exceptional times, and while it is one thing to know these pointers, implementing them into your daily life is not always as easy as it seems. Another important issue is remote teaching, which many of my colleagues were forced to tackle (and they have done so admirably) for the first time in their lives. Yet, while quickly moving seminars online takes tremendous effort not to be underestimated, teaching does provide structure to a working week. This structure is lacking for many PhD candidates who, like myself, do not (yet) teach. If anything of the above sounds familiar, you are not alone.

There are many silver linings, however. My supervisors are wonderfully supportive, and understand that we are simply not as productive as we usually would have been. It is probably best to let go that of the idea that ‘normal’ productivity — which, let’s be honest, in fact often includes overtime — is feasible given the current circumstances, but this is something I still struggle with. As concerns structure, some of the LUCAS PhD’s have started a group of ‘accountability partners’ (based on the book Grip: Het geheim van slim werkenby Rick Pastoor). In weekly meetings, we will set work and study goals for the coming week and account for the progress we have made in the previous. I have good hopes that the meetings of this group — to which a colleague of mine lovingly refers as her ‘accountabuddies’ — will add some more rhythm to the week. Stay safe (and inside)!

© Glyn Muitjens and Leiden Arts in Society Blog, 2020. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Glyn Muitjens and Leiden Arts in Society Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

0 Comments