Sex in Leiden’s Student Culture since the Golden Age

How different were students during the Dutch Golden Age? Not that much actually. Tim Vergeer discusses some historical and literary examples of the sexual adventures of some of Leiden’s students in the seventeenth century (and after).

In Theodore Rodenburgh’s play Ialoersche stvdenten (1617, ‘Jealous Students’), a group of male students engage into a courtship with three women from Leiden. The reader is confronted with an intriguing courtship display, for Juliana is in love with Cardenio, who in turn is happy to engage into intimacies with her. At the same time, Valerio is witness to the scene. A jealous man, he complains that Juliana had promised herself to him. Valerio wants to win Juliana’s heart by challenging Cardenio to a duel.

Another couple breaks up with each other, when Marcio thinks that in turn his girlfriend Celia has been promiscuous. Celia meets with her friend Tembranda, who has been left by Fabricio, although they were supposed to get married. This makes Celia say that students are ‘schallicke gesellen / Bedrieghelick en valsch, deurtrapt en vol bedroch’ (1617, fol. C3v.). That is: they are ‘rogue companions / deceitful and vicious, cunning and full of tricks’. After this rough analysis on Celia’s part, it is once again confirmed that these students are sexually liberated, when Cardenio seems to have fallen in love with Celia.

The students leave for The Hague, which in the seventeenth century was famous for its night life among young Dutch people. There, it was customary for the ‘beau monde’ to parade along the Lange Voorhout. Their aim was to see and be seen. The students do the same. The women from Leiden do not accept this, however, and decide to confront the boys in The Hague. Disguised as male students, they go to The Hague as well. After the women have successfully confronted the boys, the play settles with every couple happy in a relationship and bound for the altar.

With Ialoersche stvdenten Rodenburgh had translated Lope de Vega’s La escolástica celosa (1604) into Dutch. Although the storyline is originally Spanish, Rodenburgh relocated the play from the university town Alcalá de Henares in Spain to the university town of Leiden. In turn, Madrid became The Hague. In the moralistic message of this play, Rodenburgh is, furthermore, less disapproving of the characters’ behaviour than he had been in his other adaptations and translations from Spanish. He seems to suggest that what the reader is witness to is a realistic representation of seventeenth-century Dutch student culture (Abrahamse 1997, 98).

However, Rodenburgh had never been a student at Leiden University himself and was merely projecting this Spanish story onto Dutch student culture, with Leiden as the most representative and oldest university in the Dutch Republic.

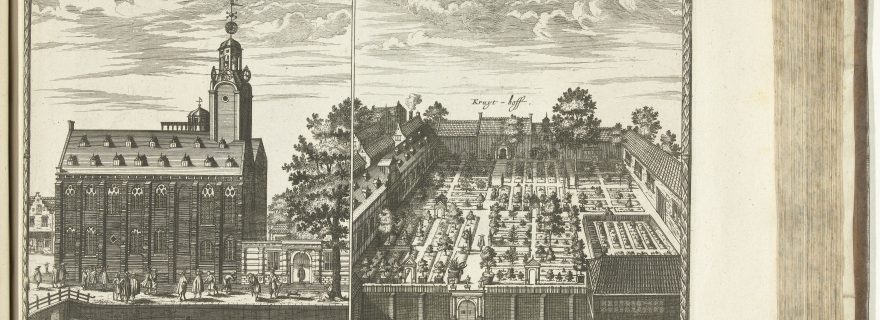

Nevertheless, Rodenburgh painted a picture that is reflected in other sources from the same period. The well-respected lawyer Johan van Heemskerck seemed to have particularly enjoyed himself during his studies in Leiden, which he started in 1617. In a poem-letter ‘Aen Johan Brosterhuysen’ written to his friend—but later published in his Minne-kunst (1622, ‘The Art of Love’)—he proposes to go skating with winter having frozen over the Rapenburg canal. From there, they could, then, skate to the Steenschuur. Nowadays, it houses the Faculty of Law and some stately buildings, but during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries this was the place where the spinsters washed and spun the wool meant for Leiden’s cloth industry. These women earned some extra money with the sexual services they provided to Leiden’s population and its student population specifically.

The play by Rodenburgh and the poem by Van Heemskerck paint the picture of a student culture that is fully decadent. This is also noted by Willem Otterspeer—the university historian of Leiden University. Inevitably, Leiden’s students had to come into conflict with the general population. Otterspeer writes: ‘Furthermore, there was a certain social tension between the local population, which was mainly Protestant and worked in the cloth industry, and the student population, which was diverse in terms of religion and primarily upper-class’ (2008, 41).

In fact, Leiden’s student culture has remained unchanged in the past four hundred years. As an alumnus of Leiden University, François HaverSchmidt wrote ‘De drie studentjes’ (‘The Three Little Students’) as contribution to the Studenten-almanak in 1859. HaverSchmidt ascribes the students the same high libido of their seventeenth-century comrades:

And only a few years ago, in 2011, an email written by a student went viral in Leiden. In his allegation, this male student complained that his supposed friend, a freshman, had shared the bed with his ex-girlfriend, something that he considered to be a sign of betrayal.[1] Four hundred years later, his allegations at the address of this freshman echo the behaviour of the students in Rodenburgh’s play Ialoersche stvdenten. Students will be students.

Further Reading

Abrahamse, Wouter, Het toneel van Theodore Rodenburgh (1674–1644). Amsterdam: AD&L, 1997.

HaverSchmidt, François, ‘De drie studentjes’, Studenten-almanak (1859), 241–250.

Otterspeer, Willem, The Bastion of Liberty: Leiden University Today and Yesterday. Leiden: Leiden University Press, 2008.

Rodenburgh, Theodore, Ialoersche stvdenten. Leiden: Bartholomeeus Jacobsz de Fries, 1617.

Van Heemskerck, Johan, Pvb. Ovidii Nasonis minne-kunst, gepast op d'Amsterdamsche vryagien: met noch andere minne-dichten ende mengel-dichten, alle nieu ende te voren niet gesien. Amsterdam: Dirck Pietersz. Voskuyl, 1622.

Van Marion, Olga, and Tim Vergeer, ‘Spain’s Dramatic Conquest of the Dutch Republic. Rodenburgh as a Literary Mediator of Spanish Culture’, De Zeventiende Eeuw. Cultuur in de Nederlanden in Interdisciplinair Perspectief 32.1 (2016), 40–60.

[1] Because of privacy issues, the email has not been quoted directly from. The text of the email is in the possession of the author.

© Tim Vergeer and Leiden Arts in Society Blog, 2019. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Tim Vergeer and Leiden Arts in Society Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

0 Comments