Visibility and Vulnerability in the Physical Space of the LGBTI+ Archive

Visiting archives is a central step in the research process of many historians. Doing archival research often starts with scouting the archive’s catalogues, and is followed by making an appointment to see that material, culminating in one or multiple visits. This process might differ per archive, depending for instance on how easily searchable the archive catalogue is, how approachable the archive is for questions, the amount of regulation during the visit, or on the physical shape of the archive.

The physical space of an archive determines the way the archive can be interpreted, experienced and accessed. Physicality is one of the factors that impacts accessibility, as it determines, for instance, whether disabled people and/or trans people are able to enter the archive, and make use of facilities such as accessible and inclusive bathrooms. Archival scholar K.J. Rawson illustrates the ways transgender visitors are seriously impacted by the absence of gender neutral bathrooms:

The physical space of the archive also shapes visitor’s experiences and imaginations in other ways. Archival scholars Gracen Brilmyer, Joyce Gabiola, Jimmy Zavala and Michelle Caswell discuss how the physicality of community archives determines “what people and stories one encounters and therefore how one imagines others.”[ii]

When community archives are housed in community centres that are also used for community gatherings and events, this influences how archive users understand these communities. Moreover, the associations archival users have with the archive, based on their individual memories of and experiences with that space, profoundly impacts the way these users will relate to the community archive, and the community itself. (Brilmyer, Gabiola, Zavala, Caswell, 2019, p. 27.) For instance, someone who has lived in Amsterdam for their entire life will relate differently to an archive of the history of Amsterdam than a visitor to the city. Likewise, visitors who have experience with the events hosted in a community archive will relate differently to the archive than those unfamiliar with the space.

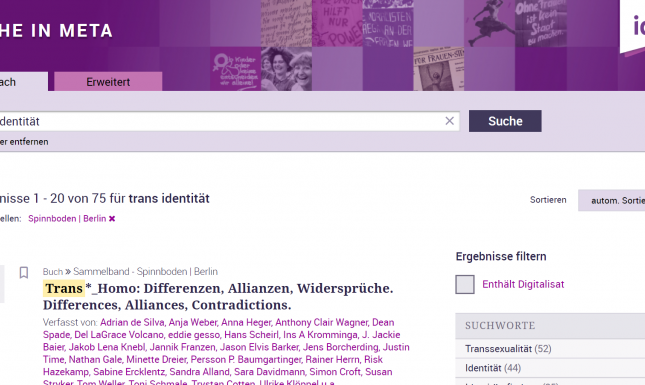

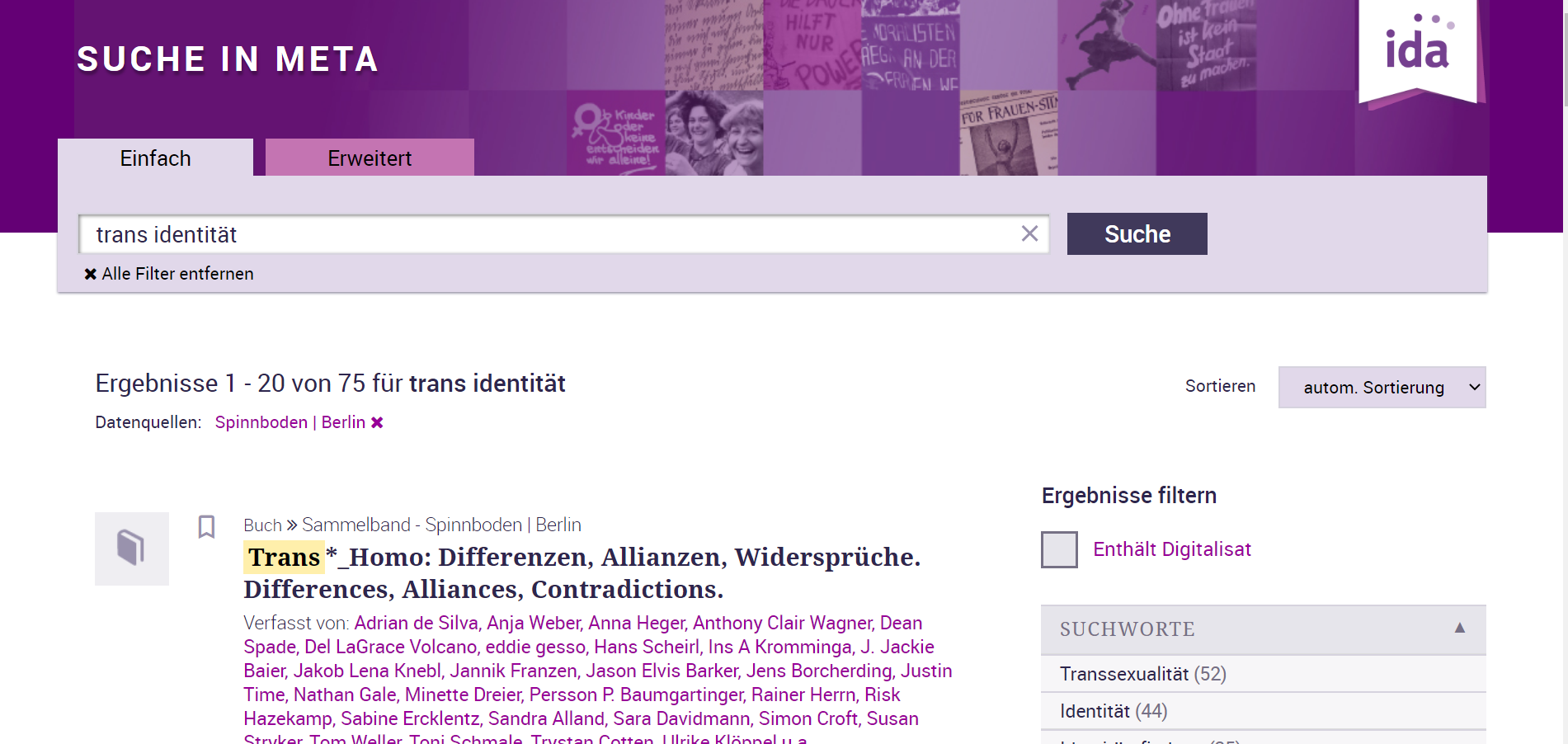

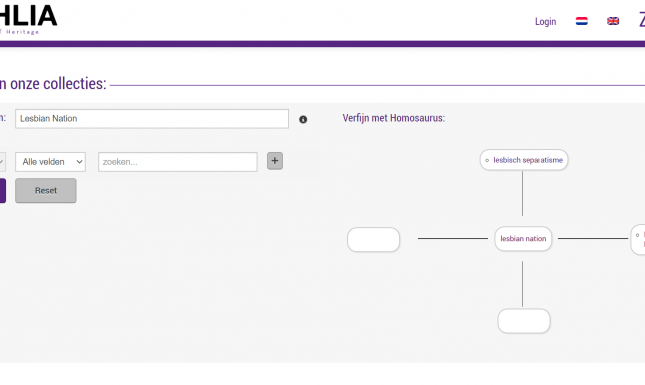

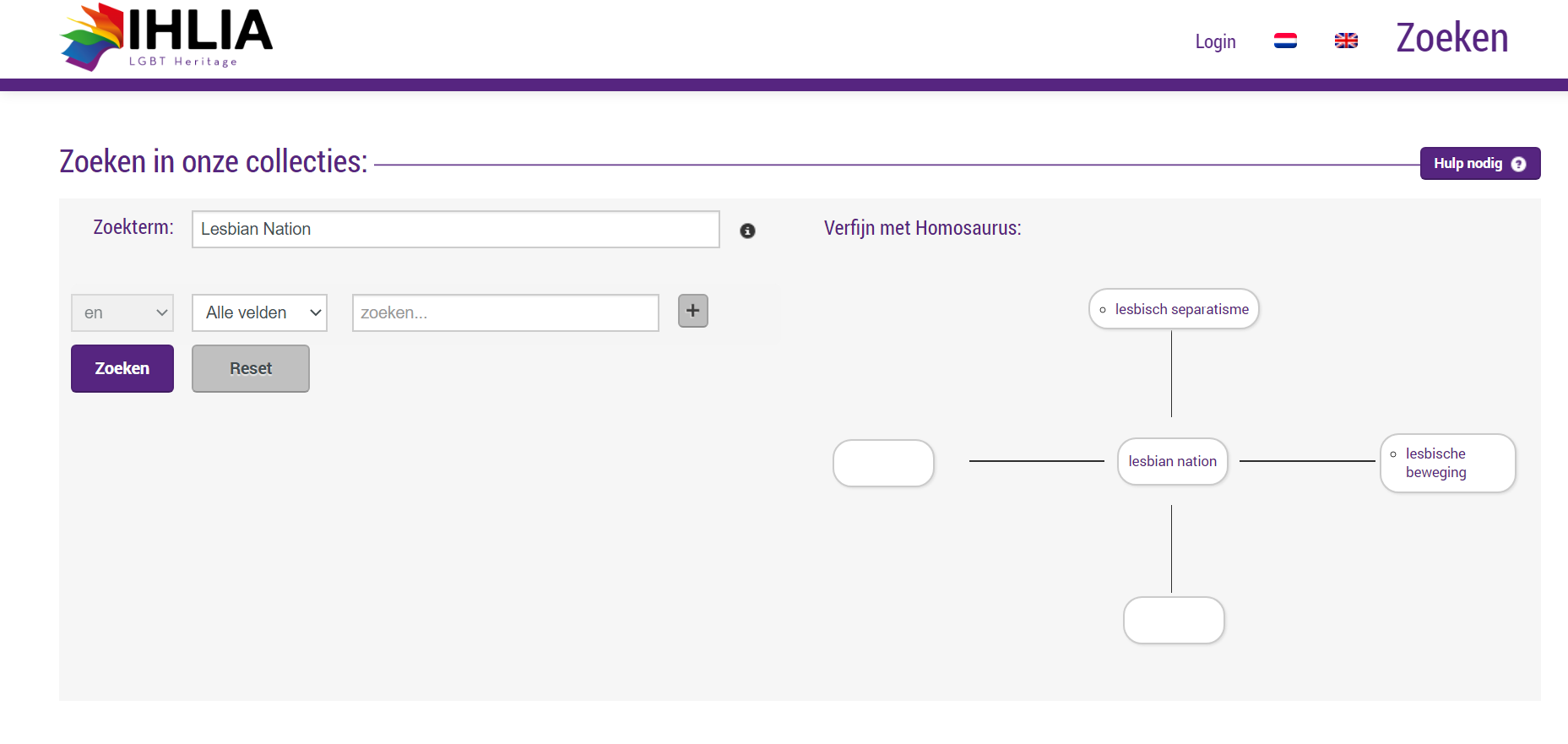

I personally experienced the impact physical space can have on research during my visits to IHLIA LGBTI Heritage, in Amsterdam, and the Spinnboden Lesbenarchiv und Bibliothek, in Berlin.

IHLIA LGBTI Heritage is located in the Openbare Bibliotheek Amsterdam (OBA), a ten minute walk from the Central Station. IHLIA’s information desk is on the 3rd floor, in the back, near the windows. While accessibility information could be improved, IHLIA is reachable for wheelchair-users, and there is an accessible bathroom on the 3rd floor. There are currently no gender neutral bathrooms, which can impact trans and non-binary visitor experiences. While the format of IHLIA’s information desk and visitor space has changed a lot over the years, it remains located in a very open space. Visitors are essentially among other ‘regular’ library visitors, seemingly mainly high school and college students. IHLIA is visible; the visitor space holds exhibitions with large images, accessible to anyone in the library. Their book collection is shelved in the regular white cabinets of the library, but IHLIA also has their own large pink cabinet, encouraging visibility. Any library visitor could come in and browse their open-shelves LGBTI+ books, or stroll through the open exhibition, without appointment.

The openness of IHLIA to any users of the library, rather than to just the LGBTI+ community, has several meanings. It is easy to stumble across them, even if (not yet) actively involved in the LGBTI+ community. This makes LGBTI+ stories and history open for anyone, also for those who are questioning or not out of the closet, and anyone who is curious and wants to learn more. Feminist and queer literary scholar Valerie Rohy points out the importance of this, arguing that “the public library gives access to an identity outside the norm. To those who can risk so public an arena, this archive offers a very private meaning.”[iii]

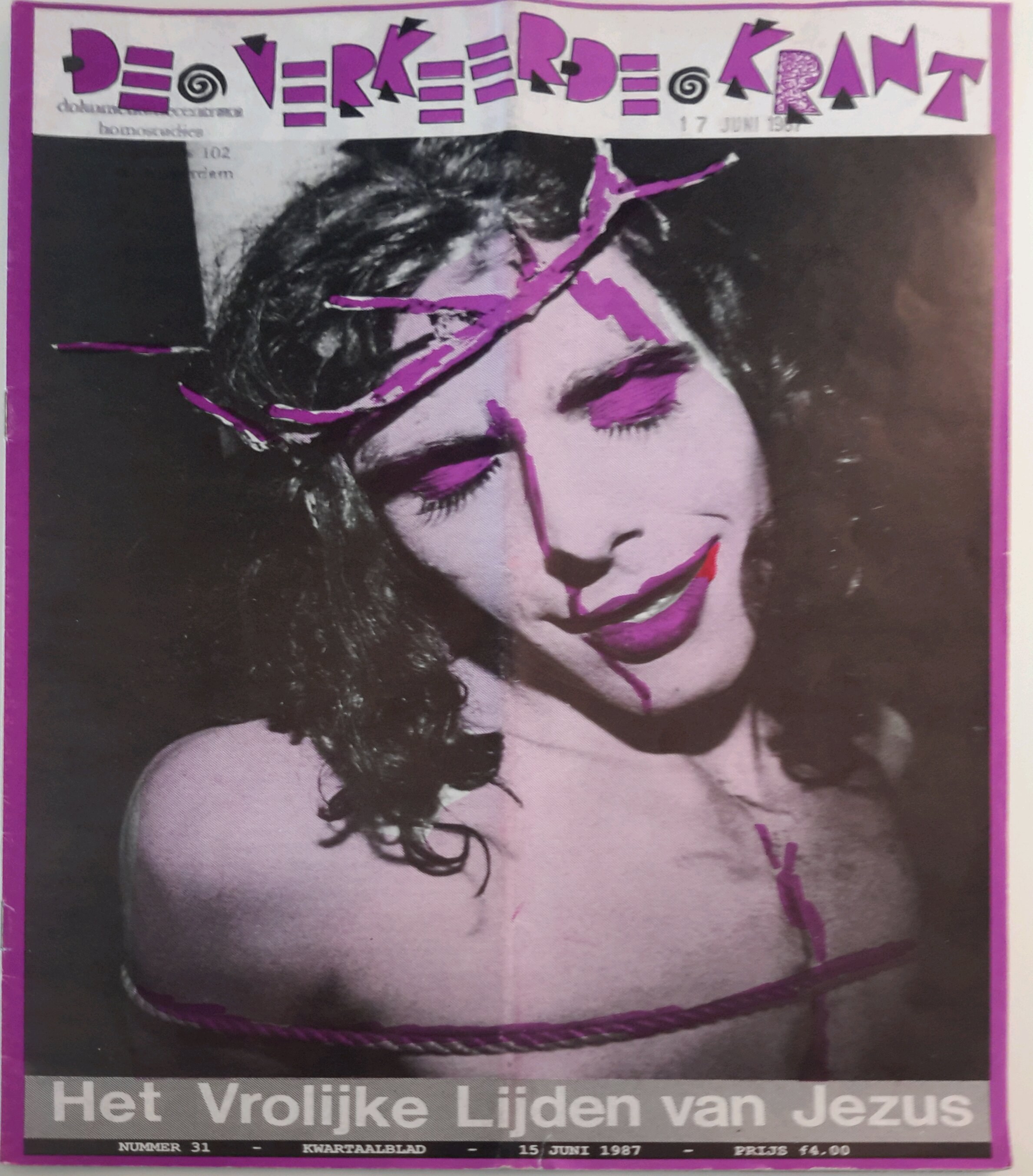

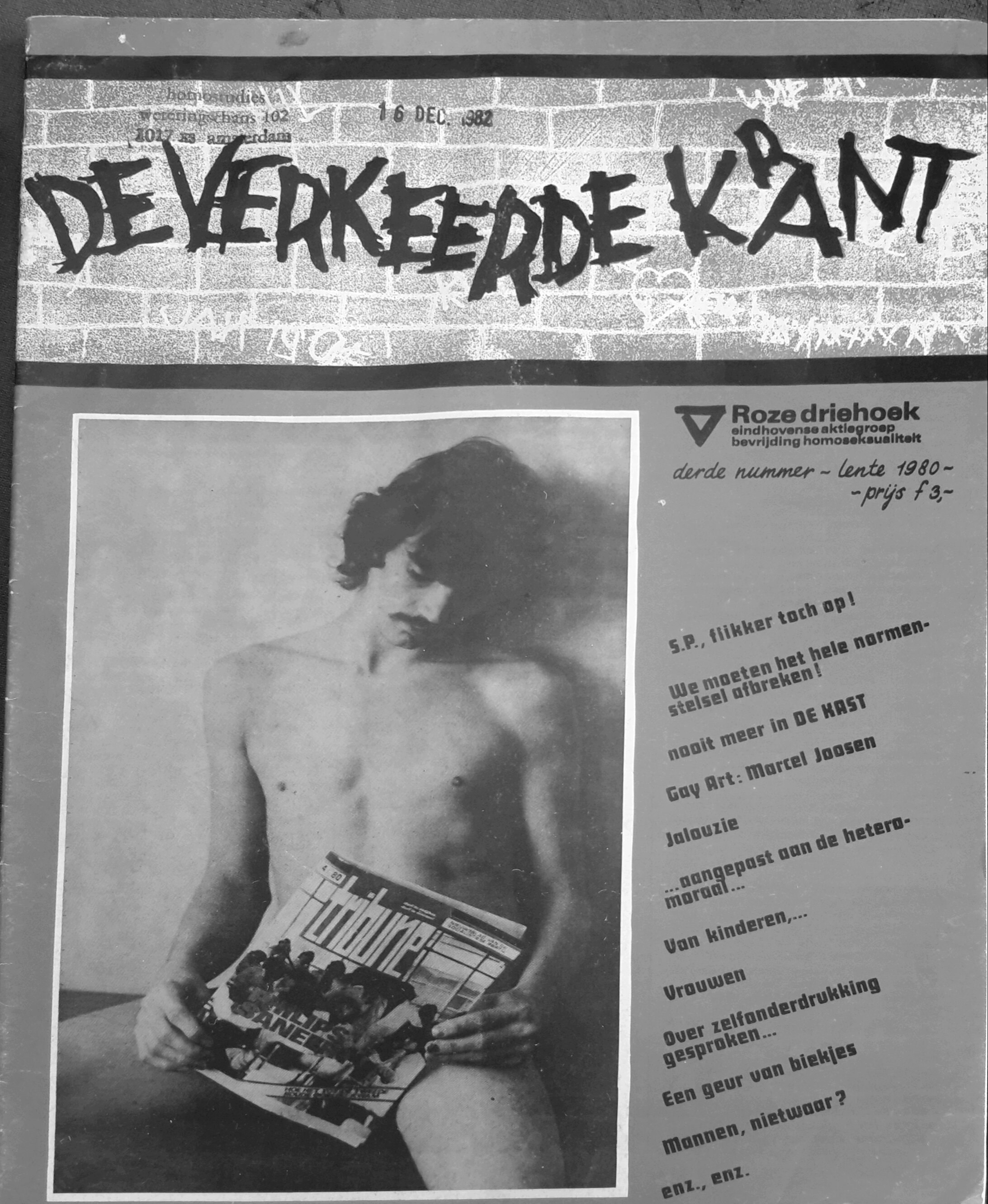

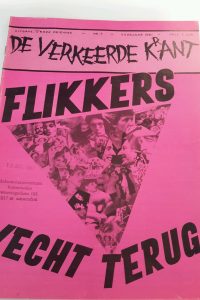

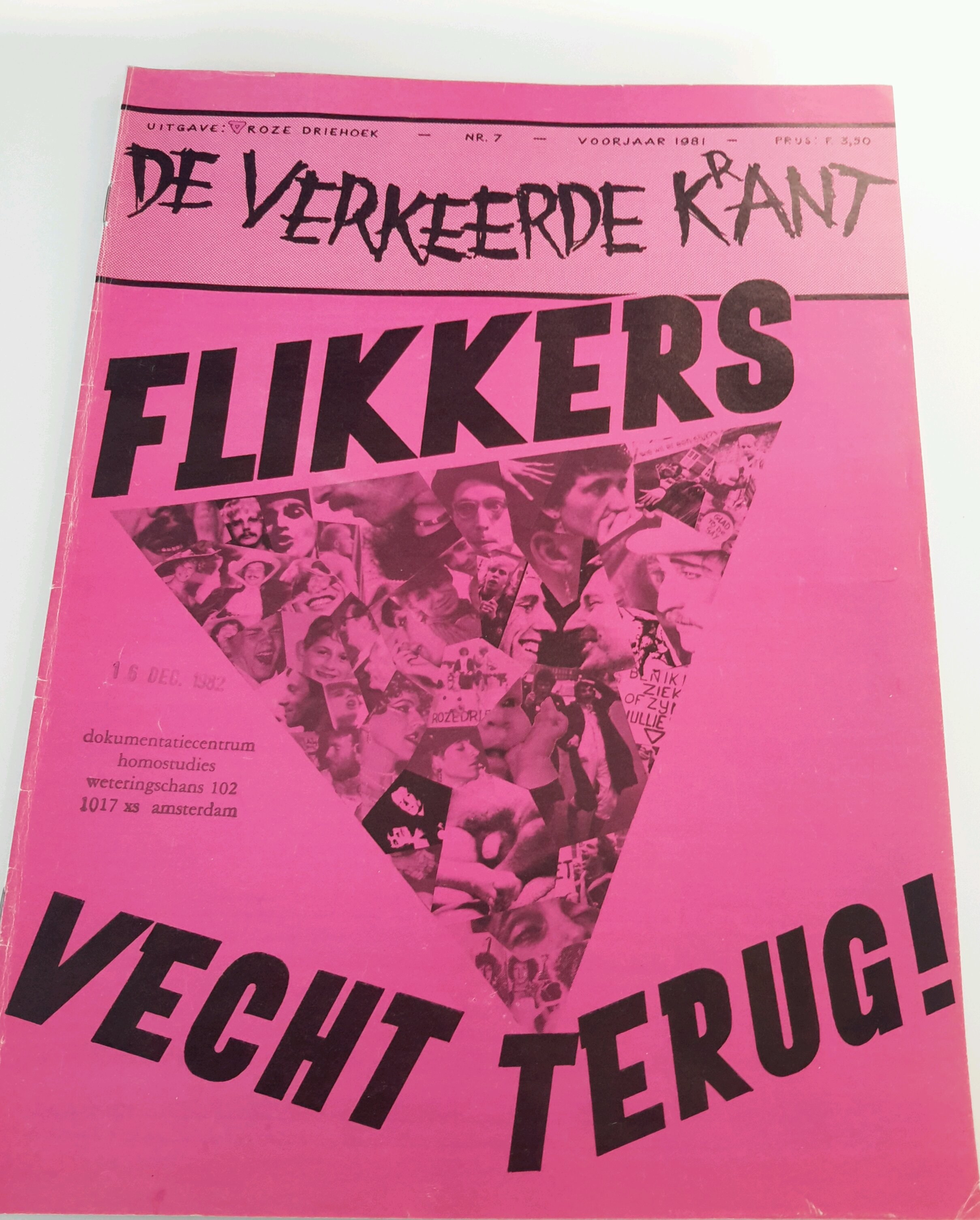

However, visitors may also find themselves exposed while visiting IHLIA. When I visited IHLIA in 2018, the visitor desk was being used by another IHLIA visitor, and I was asked to find a regular study place on the 3rd floor of the library. During this particular visit, I was looked into archival material of the Eindhoven-based radical gay group De Roze Driehoek (The Pink Triangle), most notably their magazine De Verkeerde K(r)ant.[iv]

Behind its colourful covers, De Verkeerde K(r)ant published, amongst many other things, photographs of nudity and drag. I also looked at De Roze Driehoek’s membership-only bulletin, De Sodomieter (‘The Sodomite’), which also included small cheerful drawings of genitalia and male nudity.

De Sodomieter; Intern Bulletin 1 (1979). From the collections of IHLIA LGBT Heritage.

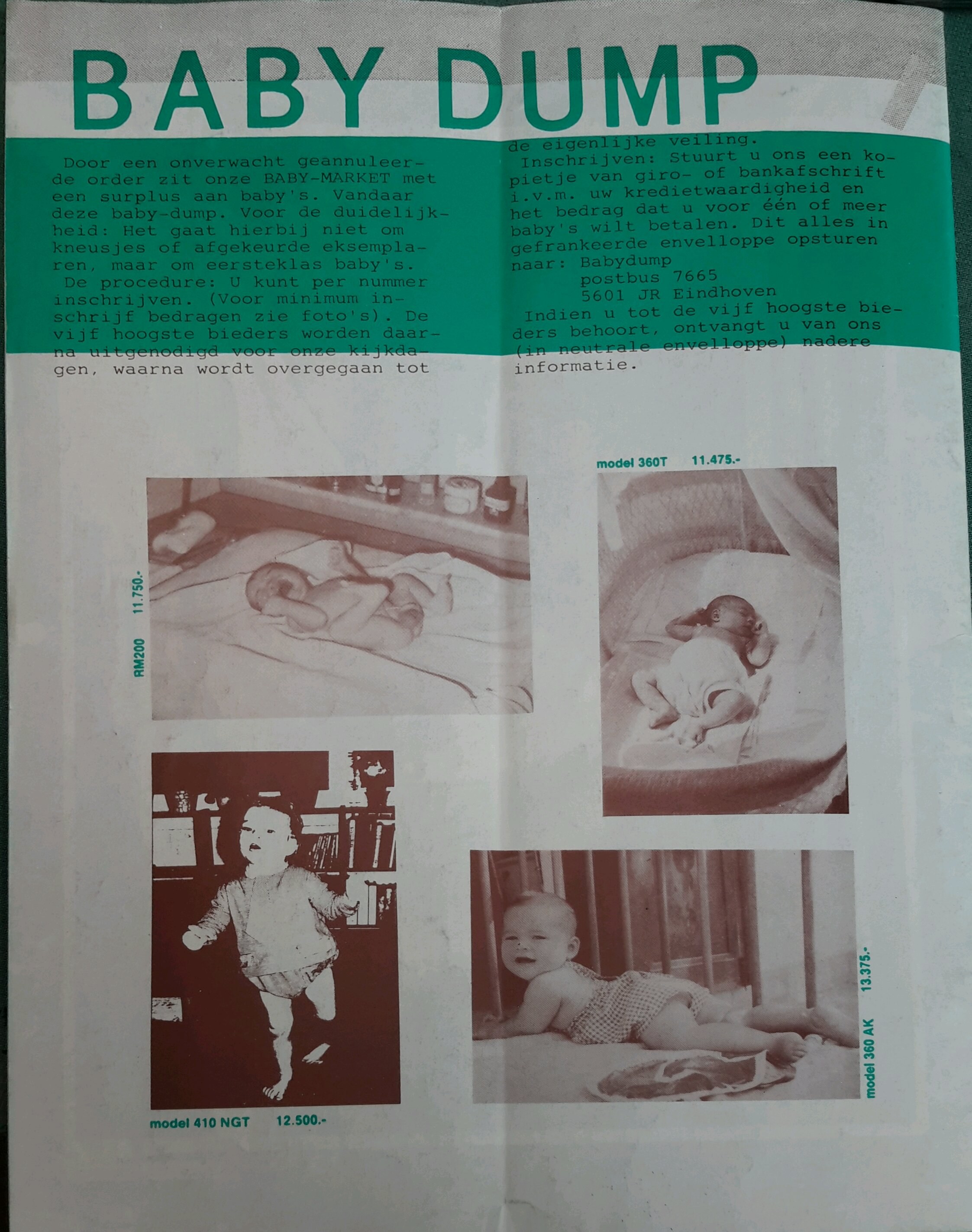

De Verkeerde K(r)ant also published deliberately controversial articles, making parody of the way gay men were perceived in mainstream society. At one instance, they published a ludic response to accusations of pedophilia, in the form of a mockery advertisement, ‘Baby Dump’, which showed supposedly ‘on-sale’ pictures of babies.

Sitting at a small table in the regular library space, surrounded by young, giggling students with their school textbooks, admittedly changed the way I was able to interact with this material. I felt nervous and rushed, and it made me feel anxious to linger on a page with explicit or deliberately controversial material. I scanned the material quickly, without taking time to read it in detail, and avoided making more high quality pictures of the material, as I usually do. Even though I am comfortably and proudly queer, and also present myself as such, accessing this material so publicly still made me feel visibly ‘queered’, and visibly nonnormative in a normative space. Moreover, I felt protective of the material, afraid to leave it even for a toilet break, in case someone around me might do something to it. Had I had my usual seat at the IHLIA visitor desk, I would have likely felt more comfortable in the already queered space of this part of the library, with the material protected by the archivist on desk-duty.

Since this moment in 2018, I have visited IHLIA many more times, for various research projects. Moreover, I have seen behind the scenes extensively, first as intern during my Master and then briefly as embedded researcher as part of my PhD-trajectory. Speaking, a few years later, with one of the archival staff members about this feeling of discomfort I experienced during this one visit, she rightly noted that I could have approached the staff on desk-duty, and ask to be seated elsewhere. IHLIA does offer ways to engage with their collection that are less exposed. Even then, however, the space influences how the visitor engages with the material – I would likely not even have considered any feelings of possible discomfort around the materials and the people around me, had I been in a different sort of space.

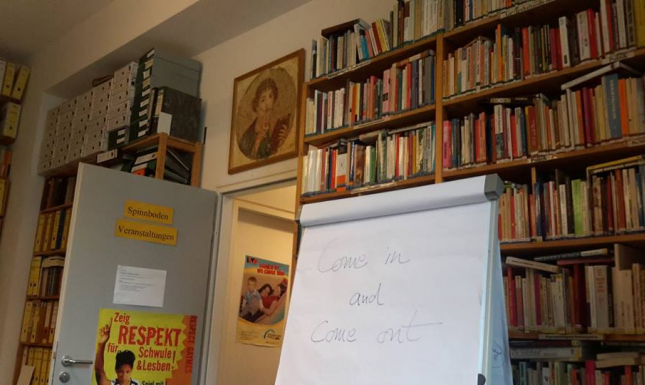

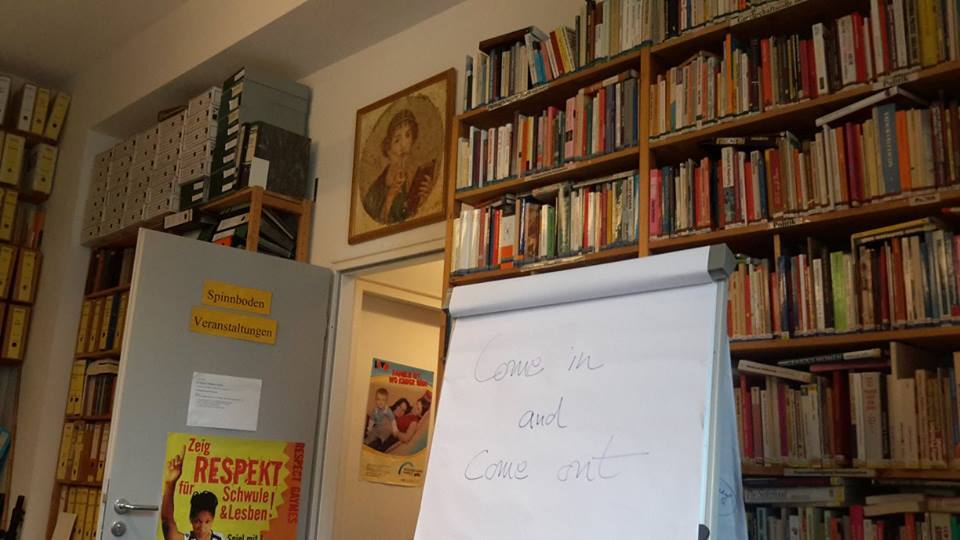

An earlier visit to the lesbian archive in Berlin, Spinnboden Lesbenarchiv und Bibliothek, in 2017, illustrates how the physicality of that archival space evokes very different questions. Spinnboden is not housed in a public library, but is accessible only to visitors with an appointment. On their website, Spinnboden gives accessibility information: they explain how to reach the archive with public transport, and that there are cobblestones in front of the entrance. The site lists information on the presence and the size of the elevator, the hight of the threshold and the availability of a ramp. The toilet in the building is not accessible, but there is a city toilet 700 metres from the archive. Additionally, there are several short videos in German Sign Language about Spinnboden on the website.[v]

Inside, Spinnboden is like a living room that is filled from floor to wall with books and maps of archival material. Back when I visited, the Spinnboden website read ‘nur fur frauen’, (‘only for women’), which has been removed for a while now. Upon entry, an archivist approached me, looking gravely worried, and explained that there was a male visitor present, but that, if I wanted her to, she would send him on his way. During my visit, the other visitor, the archivist and me were the only ones in the archive. I could take all the time I wanted with the material. In this explicitly queer living-room like space, I felt at home with the material I was accessing.

The stark regulation of visitors, however, could also have prevented easy access for closeted people, such as closeted trans women. At the time, I did not yet identify as nonbinary and presented (sort of) feminine, and I was accepted in the space as someone who had more right to be there than the male visitor, who would have been sent out on my request. I wonder now how I, as a transmasc nonbinary person, would have felt in that moment, and whether a femininely presenting visitor would have gotten the chance to send me out.

Another contrast is that there is no possibility to stumble across this material, as the Spinnboden archive is only accessible through appointment. While IHLIA makes LGBTI+ heritage more visible, Spinnboden does this, at least in its physical space, less so.

Not all LGBTI+ archives aim for increased LGBTI+ visibility. Cultural and film scholar Dagmar Brunow refers to Johanna Schaffer’s concept of this ‘ambivalence of visibility’; while visibility may empower marginalised groups, there are also increased risks of vulnerability that come with visibility and recognition (Brunow 2018). This is also what is on the balance for the visitor of IHLIA and Spinnboden: a visitor could feel empowered or exposed by IHLIA’s visibility in the public library, just as they might feel comfortable or hidden away in the Spinnboden archive. Different modes of physicality bring up different advantages and disadvantages, which impact the visitor and the way visitors relate to the material, the community, and the space around them.

These very different archival research experiences have been inspirational in envisioning my PhD research project, on the history and development of LGBTI+ archives in the 1970s, 80s and 90s, inclusivity and exclusivity in the LGBTI+ archive, and the ways the visitor can relate to and shape the LGBTI+ archive.

Note: This text has also been published in the co-edited volume: Eliza Steinbock, Hester Dibbits (eds.), Practices Matter. The Critical Visitor Book, Rotterdam: Nederlands Museum voor Wereldculturen (2024).

[i] K.J., Rawson, ‘Accessing Transgender // Desiring Queer(er?) Archival Logics,’ Archivaria 68 (2009) 127-128.

[ii] Gracen Brilmyer, Joyve Gabiola, Jimmy Zavala, and Michelle Caswell, ‘Reciprocal Archival Imaginaries: The Shifting Boundaries of ‘Community’ in Community Archives’, Archivaria 88 (2019): 26.

[iii] Valerie Rohy, ‘In the Queer Archive: Fun Home’, GLC: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies 16:3 (2010): 354.

[iv] This title is a pun that alludes to being queer, as it literally translates to ‘The Wrong Side’. The r is bracketed, making the word ‘krant’ (paper) into ‘kant’ (side).

[v] See: https://spinnboden.de/kontakt/...

References:

Brunow, Dagmar, ‘Naming, Shaming, Framing? The ambivalence of queer visibility in the audio-visual archives’, In: Koivunen, Anu, Kyrölä, Katariina & Ryberg, Ingrid eds, The Power of Vulnerability: Mobilizing Affect in Feminist, Queer and Anti-racist Media Cultures. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2018.

© Noah Littel and Leiden Arts in Society Blog, 2024. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Noah Littel and Leiden Arts in Society Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

0 Comments