Who was Amsir? A Colonial Portrait by Jan Veth (1864-1925)

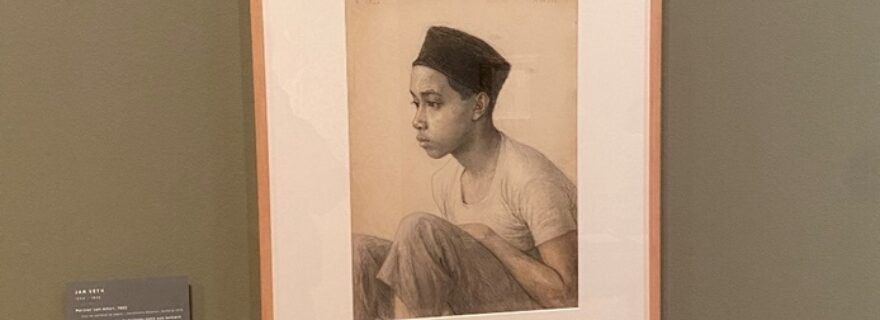

In the exhibition on Dutch artist Jan Veth, which recently opened at the Dordrechts Museum, Veth’s colonial work is made visible. In this blog Nick Tomberge uses Veth’s Portrait of Amsir (1922), on display at the exhibition, to discuss how the museum presents the colonial past to the general public.

On February 18 this year, a retrospective exhibition of work by the Dutch artist Jan Veth (1864-1925) opened at the Dordrechts Museum. Among his most widely known works is undoubtedly the early portrait of the writer Albert Verwey from 1885. In comparison, the paintings and drawings that resulted from Veth’s journey as a painter-tourist in the former Dutch East Indies in the early 1920s enjoy much less fame. This work has long remained out of focus in the literature (e.g. Haveman, 2005). As a result of increased social and scholarly attention to the colonial history of the Netherlands, Veth’s Indies portraits and landscapes seem to have stepped out of the shadows. The recently published edition of Johan Huizinga’s biography of Jan Veth, unlike previous editions, also includes colour reproductions of Veth’s colonial work (Huizinga, 2022). In addition, the Dordrechts Museum has made the journey of Jan Veth and his wife Anna Veth-Dirks to their daughter and son-in-law who had been living in Java for several years one of the highlighted episodes that informs the selection and presentation of the work. The current exhibition includes Veth’s painting of the Borobudur (a Buddhist temple in Central Java) and his portrait of the Javanese Amsir.

The text sign accompanying the latter work informs viewers that Veth probably made the drawing at the end of his journey. Visitors to the exhibition will not learn anything else about Amsir’s background. In his drawing, Veth has detached Amsir from his time and everyday environment (similar to the colonial portraits made by western anthropologists). The text panel next to it states that ‘[t]here is nothing more known than the boy’s name’. The book published to commemorate the exhibition does not discuss the portrait either (Reid, 2023). Nor are viewers prompted to reflect critically on the unequal intercultural encounter of which the drawing is the manifestation (cf. Basu 2022). For instance, visitors are not encouraged to reflect on the precise circumstances under which Veth portrayed Amsir, and which allowed the painter to fulfil ‘his desire to portray Indonesians’ (as the exhibition label states).

The way the drawing is now displayed maintains the colonial hierarchy that gave Veth the opportunities to create his work and does not offer a multi-voiced perspective on the colonial past. If there really were nothing more to be said about Amsir, attention could at least be drawn to the fraught history that led to the portrait and the lack of Amsir’s biography. In addition, alongside Veth’s portrait, there might be room for a ‘response’ by an Indonesian artist, confronting the viewer with the unequal power relations in which Veth’s colonial art is rooted. Recently the Amsterdam Museum employed such strategies in their exhibition Colonial Stories.

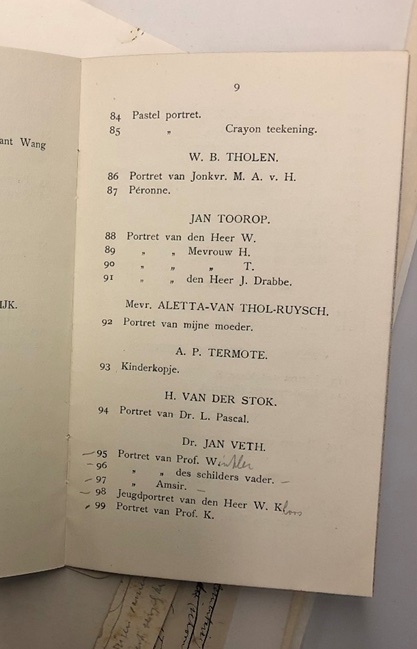

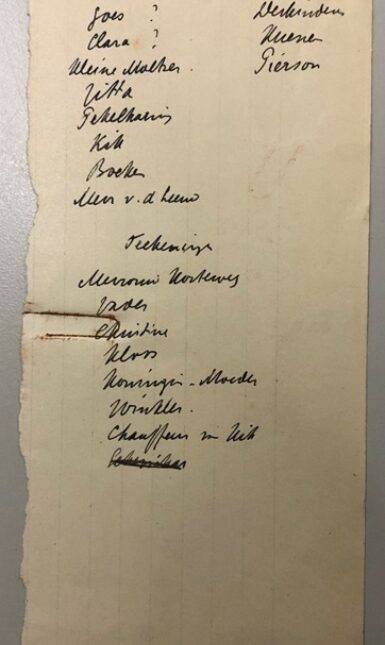

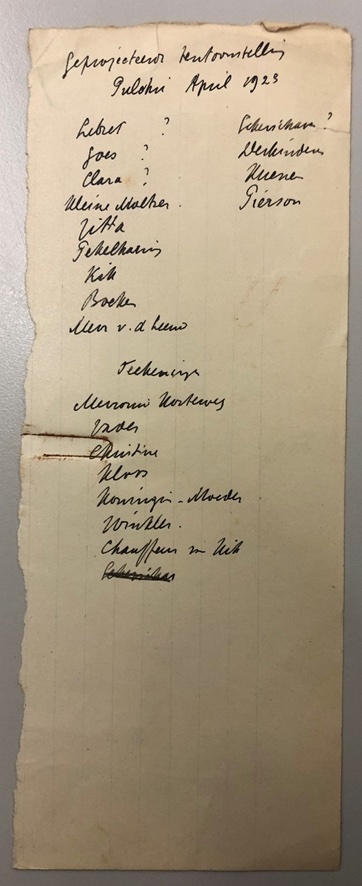

However, more can be said about Amsir based on archival documents in the Jan Veth Archive which is kept in the Netherlands Institute for Art History (RKD) in The Hague. In an archive folder labelled ‘Dürer,’ there is a loose piece of paper between Jan Veth’s notes on the German painter and printmaker. Although one side includes notes on Dürer’s letters, on the other Veth noted the works that he planned to exhibit in April 1923 at the artists’ association Pulchri Studio in The Hague. At the bottom of his list he wrote ‘Chauffeur van Kik’ [Kik’s driver]. Jan Veth’s daughter who lived in Batavia, the former capital of the Dutch East Indies, was named Saskia, but her nickname was Kik. The archive also contains a printed brochure of the exhibition, which includes only one of Jan Veth’s Indies drawings: his Portrait of Amsir. Jan Veth thus portrayed the chauffeur of his daughter and son-in-law during his trip through the Dutch East Indies.

Further information can be found in the surviving letters that Saskia Delprat-Veth sent from Java to her parents in the Netherlands. In these letters, which are kept in the Regional Archives Dordrecht, she writes that soon after her arrival in Java, she and her husband, Daan Delprat, purchased a Hudson brand car and employed both a driver and an assistant driver (Delprat-Veth to A. Veth-Dirks and J. Veth, April 15, June 25 and July 3, 1920). Only of the driver does she give the name in various spellings: ‘Mejin’ and ‘Mein’ (Delprat-Veth to A. Veth-Dirks and J. Veth, June 25, 1920, November 11, 1921). Amsir’s name does occasionally appear in the letters, but without then mentioning his activities (Delprat-Veth to A. Veth-Dirks, April 2, 1924). It is likely that Amsir earned his money as an auxiliary driver; Mejin continued to work for Saskia Veth and Daan Delprat for many years. Like most of the Delprat couple’s other servants, Amsir lived in the servants’ quarters with his family in the back yard of the residence (Delprat-Veth to A. Veth Dirks, June 10, 1920). Among the Indonesian staff who worked for the Delprats, they were the poorest. According to Saskia Veth, when they moved into her yard, their total belongings consisted of only an empty gasoline can (Delprat-Veth to A. Veth Dirks, April 5, 1921). In order to celebrate his wedding, Amsir had to ask his employers for a large advance (Delprat-Veth to A. Veth-Dirks, April 2, 1924).

Although Saskia Veth frequently writes about her chauffeur and assistant chauffeur in her letters to her parents, the passages about Amsir are so coloured by contemporary colonial discourse that we cannot possibly distil a biographical portrait from these texts. The letters portray Amsir, like the other Indonesian servants, as ‘childlike,’ ‘animal-like,’ ‘lazy’ and ‘mendacious’. For example, although the car facilitated making the obligatory visits to friends and acquaintances, Saskia Veth wrote to her parents that owning it also came with ‘great burdens,’ as the driver requires ‘close scrutiny’ (Delprat-Veth to A. Veth-Dirks and J. Veth. May 19, 1920). When the driver’s assistant behaves unsympathetically, she writes, she scolds him, then notes with satisfaction that the rest of the staff start working harder out of fear (Delprat-Veth to A. Veth-Dirks and J. Veth. January 18, 1921).

The colonial sources used do not bring us closer to the Javanese Amsir who earned his money as a (co-)driver. However, they do shed more light on the power relationship that existed between the painter Jan Veth and his Javanese model Amsir. In addition, they reveal the discourse that in colonial times fuelled the belief among Europeans that the prevailing status quo should be maintained. Saskia Veth’s precise control over her Indonesian drivers can be read as a metaphor for the leading role that the West in the colonial perspective should take vis-à-vis the East. The passages fill us today with a certain discomfort, but that is the discomfort behind Veth’s Portrait of Amsir that would also have deserved to be shown to museum visitors.

References

Basu, Paul. “Art as Colonial Contact Zone.” Stedelijk Studies, March 29, 2022, https://stedelijkstudies.com/a....

Delprat-Veth, Saskia and Daniel A. Delprat. Letters to Anna Veth-Dirks and Jan P. Veth. 1919-1921. Collection of documents related to the painter Jan Veth. GAD 545, inv. no. 766. Regional Archives Dordrecht.

Delprat-Veth, Saskia and Daniel A. Delprat. Letters to Anna Veth-Dirks and Jan P. Veth. 1922-1924. Collection of documents related to the painter Jan Veth. GAD 545, inv. no. 188. Regional Archives Dordrecht.

Haveman, Mariëtte, chief ed. Kunstschrift 49, no. 1 (February/March 2005).

Huizinga, Johan. Leven en werk van Jan Veth (Amsterdam: Querido, 2022).

Pulchri Studio, Tentoonstelling van portretten door leden van het genootschap. April 1923. Box 6, Folder ‘Diversen w.o. Rembrandt’. Jan Veth Archive. NL-HaRKD.0309. RKD ‒ Netherlands Institute for Art History, The Hague.

Reid, Nina. “‘Grandioos liefelijke monumentaliteit’. Jan Veth en Nederlands-Indië.” In Fusien Bijl de Vroe, Claire van den Donk, Rudi Ekkart, Quirine van der Meer Mohr, Nina Reid, and Annemiek Rens, Het oog van Jan Veth: Schilder en criticus rond 1900 (Zwolle: Waanders Uitgevers, [2023]), 192-195.

Veth, Jan. ‘Geprojecteerde tentoonstelling Pulchri April 1923’. Box 6, Folder ‘Dürer’. Jan Veth Archive. NL-HaRKD.0309. RKD ‒ Netherlands Institute for Art History, The Hague.

0 Comments