Dancing on Ruins: Rome’s political afterlife

Vast and powerful, the Roman Empire has always been used as a parallel for modern politics. These days, however, Rome might just need a PR-campaign.

Looking back at European history, it is almost as if Rome never fell. While the ultimate demise of the western Roman Empire is generally dated to 476 CE, even in the 18th century Edward Gibbon’s famous, multi-volume opus The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire discussed events throughout the European Middle Ages, the period of the crusades, and into the dawn of the Renaissance. This extra 1000 years can be explained by Gibbon’s choice to include not only the fall of the western Roman Empire, but also that of the East, which has also become known as the Byzantine Empire. This last part of the Roman Empire did not disappear until the conquest of Constantinople by Mehmed II “The Conqueror” in 1453 CE, who would in turn refer to himself as Kayser-I Rum, Caesar of the Romans.

Even after the fall of the Byzantine Empire, however, Rome has lived on in its successors almost from the very moment its power started to decline. In western Europe, the Holy Roman Empire explicitly laid a claim to the legacy of Rome, and continued to carry that torch until its dissolution in 1806. Benito Mussolini famously referred to his fascist Italy as "the third Rome", claiming both the Rome of the emperors and that of the popes as his direct predecessors.

Given this long history, it is hardly surprising that the European Union has come to be seen as the Roman Empire’s newest iteration: both are generally regarded as centralized political entities spanning the majority of the continent, which – for good or for ill – have had a significant cultural, legal and political impact on the territories they controlled. What ís surprising, on the other hand, is that Rome has also become an extremely attractive point of reference for the same right-wing politicians and opinion makers who otherwise revile the EU for being overly domineering and – dare I say – imperialistic.

The vision of ancient Rome that has emerged in these circles is, however, a highly specific one: once again, Rome has come to represent ‘our culture’, and in this context it is remarkably not Rome’s glory and power that is most often evoked, but its fall. Leaving aside the more unhinged commentators who claim that Rome was brought to its knees by feminism, what stands out most is that the Roman Empire (all 6.5 million square kilometres of it) is overwhelmingly seen as mono-cultural – and especially white.

Image 3 – “Roman Britain” by BBC Teach.

This summer, it once again became abundantly clear how important it is for certain groups to see Rome as in some way ‘ours’, when the BBC released a short animated video meant to teach children about life in Roman Britain. While the cartoon lasted barely six minutes and was completely innocuous by most standards, certain corners of the internet were outraged nonetheless, specifically because the main character’s father – a centurion working on Hadrian’s wall – is portrayed as being black.

Among others, the notorious right-wing radio personality and conspiracy theory enthusiast Alex Jones took to YouTube to accuse the BBC of a lack of historical accuracy, as well as succumbing to political correctness. A similar point was brought forward in a Twitter argument between statistician Nassim Taleb and historian Mary Beard, the latter of whom argued that ethnic diversity in Roman Britain was only to be expected.[1] Historian Mike Stuchbery likewise argued that the BBC-cartoon was historically correct, and added that “Roman Britain was ethnically diverse, almost by design”.

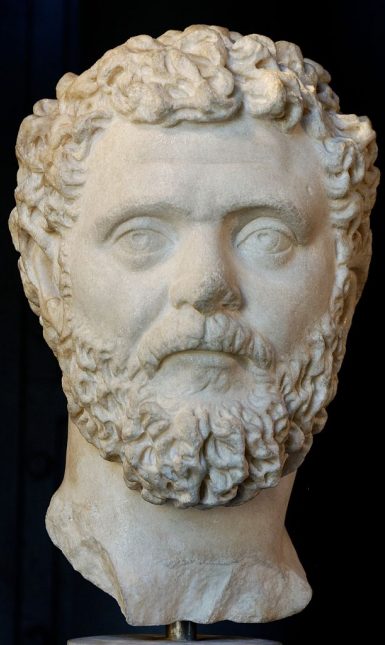

There is, indeed, plenty of evidence to suggest that inhabitants of all parts of the Empire were involved in the higher political and military echelons, and that this was actively encouraged in order to create cohesion between capital and provinces. Rather than seeing ethnic diversity as an integral part of the Roman Empire, however, many modern commentators and politicians cite it as the primary cause for Rome’s fall. Dutch politician Thierry Baudet even went so far as to state that “at a certain point, there was no ethnic Roman left”, adding that today’s Italians look nothing like the busts of Roman emperors. Departing prime-minister Mark Rutte made a similar point in 2015, when he suggested that the EU would be at great risk if it failed to protect its borders like the Roman Empire before it.

Image 6 –“What can ancient Rome teach us about the migrant crisis”, by BBC Newsnight.Certainly, the fall of the Roman Empire has also been used to make an entirely opposite point: some historians have argued that an ungenerous treatment of migrants was the true cause of Rome’s fall. However, the general public’s assumption seems to be that the states of western Europe, as heirs to the Roman Empire, should do their best to protect themselves from ‘the outsider,’ lest their legacy be threatened. In that sense, our time is not so very different from that of the early 20th-century historian Francis Haverfield, who popularized the theory of Romanization and claimed that, unlike the Greek-speaking East of the Mediterranean and particularly Egypt, the West was “racially capable” of accepting Roman culture.[2]

If there is a lesson that should be learned from history, it is probably that the legacy of Rome continues to be used to confirm modern prejudices and make modern political statements. We can only hope that today’s historians will continue to correct such tendencies – one children’s cartoon at the time.

Notes

[1] For Beard’s own version of events, see her <blogpost on the issue <https://www.the-tls.co.uk/roman-britain-black-white/>>.

[2] Haverfield, Francis, The Romanization of Roman Britain (Oxford, 1912₂), 12.

© Renske Janssen and Leiden Arts in Society Blog, 2016. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Renske Janssen and Leiden Arts in Society Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

0 Comments