Meditation on/in the Museum

Last month, museums reopened in the Netherlands. Based on her experience of visiting Museum De Lakenhal, Lieke Smits reflects on the role of museums in mental well-being.

About a month ago, Liselore Tissen published a thought-provoking blog post on the post-covid museum. She argued against the idea that authentic experiences of art can only take place in the physical space of the museum. While I do wholeheartedly agree with this conclusion, I do belong the 25% of Dutch people who, according to the National Museum Research, strongly longed for the experience of a museum visit. In this post I would like to reflect on the therapeutic function of the museum from the perspective of my own experience of visiting a museum for the first time in months this June.

When museums were closed, I thoroughly enjoyed online ways to engage with art and museums. I watched several museum vlogs, for example those from Thuismuseum. I discovered I prefer vlogs over other types of virtual tours, because ‘walking along’ with someone gives me a sensation of actually being there. The videos do not always allow for a detailed view of all the artworks exhibited, but are effective in getting across the story that an exhibition or museum tells. This made me realize that I do not necessarily go to a museum to admire artworks up close. Rather, I visit museums to find connections between the different works that are exhibited, and to find out which new perspectives the museums has to offer.

Visiting Museum de Lakenhal

On a Tuesday morning in the beginning of June, I visited Museum De Lakenhal, the Leiden municipal museum with an art collection spanning the medieval period until te present day. I had been feeling quite stressed for several reasons, including but not limited to the state of the world, academic job insecurity in a recession, and the perils of maintaining work life balance when all activities take place in the same space. When I entered the museum, I suddenly felt more at peace than I had felt in days, perhaps weeks.

Ignoring the temporary exhibition, which was too crowded for my taste, I decided to wander around the museum’s permanent exhibition. As I was already quite familiar with the collection, I felt no pressure to look at every artwork or read all the text signs. I often had an entire room or even floor to myself, which certainly contributed to the serenity I experienced. My own experience of the therapeutic function of the museum urged me to look for connections between artworks and (mental) health, and ponder the therapeutic role of museum. I would like to continue this blog post with a brief ‘tour’ of two of my encounters with artworks in the museum.

Medieval Meditation and Mental Health

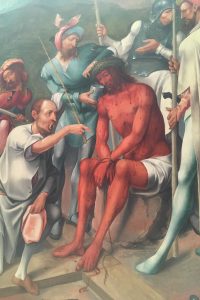

As a medievalist, I am prone to linger in De Lakenhal’s ‘Lucas van Leyden Room’, displaying medieval and Renaissance artworks. This time, my attention was caught by the bloody body of Christ, seated on a stone, resting on his way to the Crucifixion. My first response was affective; Christ’s red body is a powerful image. But soon the art-historically trained part of my brain took over, and I started interpreting the image. Being displayed on the outer panel of an altarpiece, this scene would have been visible throughout most of the year, since altarpieces were usually only opened on feast days. Thus, the churchgoers would have been intimately familiar with this depiction. In the medieval tradition of ‘affective meditation’, images of the passion were used as focus points for meditation, in which imitation of and compassion with Christ’s suffering. This spiritual work was thought to benefit the soul’s spiritual journey, and thus contribute to spiritual health. This led me back to my more affective response. Seeing Christ carrying the sins of humanity felt very apt to this present moment in history. Thus, my experience of the artwork was informed both by my personal circumstances and feelings and by my academic background, and the two worked together in creating a more layered appreciation. But somehow, the personal side of this felt less valid than the scholarly.

Seeing this image in the museum context must be very different from the medieval, sacral experience. However, our society does have a notion of the museum as a ‘temple of art’, rooted in nineteenth-century romanticism. While the religious connotations are mostly gone, a museum is still seen as a place for contemplation. Just as in the late Middle Ages, there is a therapeutic side to this. A good example of this is Slow Art Day, when museum visitors are encouraged to focus only on a few objects, and spend a considerable amount of time (a minimum of 10 minutes) in front of each artwork. The Slow Art experience is explicitly not about expert knowledge of the work, but about the visitors’ sensory and emotional repo senses. This may sound a lot like mindfulness, and many do indeed claim it can offer similar psychological benefits. Slow Art is even offered as therapy. The health benefits of art and museums in general are widely acknowledged. The Rijksmuseum ran an exhibition titled ‘Art is Therapy’ in 2014, and numerous studies have shown that not only artworks themselves, but also the physical and social museum environment can function therapeutically.

A Moving Encounter

A second artwork in De Lakenhal that captured my attention was a contemporary video piece by Koen Hauser, titled Amethyst. Lasting more than 6 minutes, this moving picture automatically invites the Slow Art method. The video shows a woman whose face slowly transforms into an amethyst, accompanied by calm, minimalist music. The video touches on universal themes such as beauty and decay, while the knowledge that the model, Valentijn De Hingh, is one of the first Dutch trans models gives rise to reflections on contemporary society and our gender and beauty norms.

Amethyst by Koen HauserWhat I found most impressive in that moment following a period of social isolation, however, was simply the act of looking another human being in the eye. The woman’s vulnerability felt inviting and functioned as a mirror. It might have been the melancholy of the music, but I started musing about the human condition and how even in times of anxiety, loneliness or isolation those experiences connect us to others. These thoughts were not very academic, but rather grounded in the Slow Art method, favouring sensations and emotions over expert knowledge. Letting go of the art historical lens through which I am used to looking at artworks felt liberating, and inspired this blog post, which is more personal than what I would normally write.

When I returned home from the museum, I tried to recreate my experience by watching Amethyst on YouTube. It was not the same. Not only the size of the screen, but also the sensation of standing alone in a spacious, empty museum room and the connections I made with other works I had seen, contributed to my initial experience. The museum environment allowed for a personal rather than purely professional enjoyment of art, the value of which academics can easily forget. I do certainly not believe that visiting a physical museum is the only or correct way to experience art, and I greatly appreciate all efforts to make art accessible by bringing it into people’s living rooms. I am, however, also very grateful that museums are open again.

© Lieke Smits and Leiden Arts in Society Blog, 2020. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Lieke Smits and Leiden Arts in Society Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

0 Comments