The many meanings of reading (1). Sonority

The term 'to read' is used for a myriad of activities. In this series, I will explore the different uses of the word in the context of book history. Today's post: silent vs oral reading.

Sitting at my desk, elbows on the page, chin on my hands, abstracted

for a moment from the changing light outside and the sounds that rise

from the street, I am seeing, listening to, following (but these words

don’t do justice to what is taking place in me) a story, a description, an

argument. Nothing moves except my eyes and my hand occasionally

turning a page, and yet something not exactly defined by the word ‘text’

unfurls, progresses, grows and takes root as I read.

Alberto Manguel, A History of Reading, p. 28.

Nowadays, most able-bodied readers will be familiar with Manguel's description of reading. Our modern experience can be summarised as follows: grab a book, sit or lie down, and delve silently into the text.

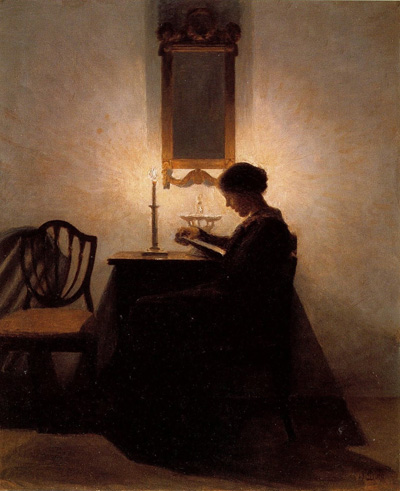

Delving silently into the text, Woman Reading by Candlelight, Peter Vilhelm Ilsted, 1907, public domain.

This operation knows some alterations as we also read magazines, newspapers, and screens. The shape of the codex and the type of material where the text finds itself, also called support material, are not the only elements in the process that have seen variations. In some occasions the reading is not done silently nor by ourselves. For example whereas adults usually read in silence, less-abled people or children are read to, while some people listen to an audio book.

These variations are not limited to our present-day time. Thus when studying the human activity of reading at a specific period and place, the different meanings of ‘reading’ must be considered. My research focuses on the actions defined as 'reading'—predominantly in Roman-character writing systems—and what they entail. I will explore these variations in a series of blogposts, including a crucial discussion on which objects can be read vs which can be interpreted. The literary experience of interpreting the text will not be dealt with, as I focus on the process in the moments before interpretation.

Silent vs oral

Saint Anne requesting silence, Saint Anne (detail), Anonymous (Faras), 8th century, National Museum Warsaw, public domain.

A significant variation in reading can be found in its sonority. Today, a person reading aloud in the library would be frowned upon and kindly asked to be quiet out of respect for the other patrons. We are so accustomed to consider reading as an individual and silent activity that it is difficult to imagine people reading to themselves out loud. However, the oral form of reading has been predominant during many periods in history.

Antiquity and Middle Ages

In Antiquity, individuals usually read texts-out loud (orally), whether to themselves, or to an audience, as it happened in public readings among the literate. The predominance of the oral form is suggested by the type of rhythmic prose found in many texts, the roll-form of books—which implies reading from beginning to end—, observations made by contemporaries, and pictographic sources. Reading in this period was also sometimes done silently, specifically when consulting a text for references. According to to Paul Saenger, early Christians divided the New Testament in chapters and preferred the codex to the roll seeking ease of access.

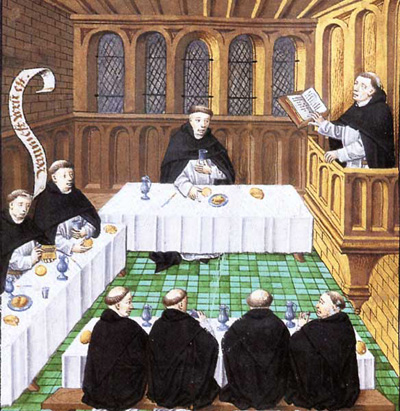

During the Middle Ages reading orally, in groups or mumbling to oneself, was highly common (although it was not the sole form). Until the twelfth century, monks would both compose and read texts orally as a group activity. Yet as texts increased in complexity, reading silently—or mumbling to oneself with gestures—became more frequent both inside and outside the monastery. In general, oral reading was characteristic for specific social settings such as in monastic and educational contexts (where it’s still nowadays also practised!); or when the text required a slow pace, for example for a better understanding of certain texts.

A lector reading during the meal. (Henri Suso, L'horloge de Sapience (1455-1460), Bibliothèque royale de Belgique, Manuscrits IV.111, folio 274)

For edification and enjoyment

As learning became an individual activity centred around more complex texts, and printed materials became more accessible, reading practices shifted towards silent mode. Yet its oral form did not disappear from the public sphere.

Reading aloud was a part of the social movements from the nineteenth century. In small workshops or large factories, a worker would read texts out loud to their colleagues, whom sometimes got a say in the books to be read. The audience even compensated the reader for the income they had lost as they were reading instead of working. Although the oral readings were also just a way to pass time during repetitive work, their main purpose of these oral readings was labourer’s education. At first, authorised by factory owners, the readings were prohibited as they became more politicised. The ban from the work floor didn’t make the readings disappear: they simply moved into clandestinity or other communal settings.

Reader at a tobacco factory in Tampa, 1930, University of South Florida Special Collections, copyright © 2001-2012 by the University of South Florida. Educational Use.

Another form of oral reading prominent in the nineteenth century was reading to friends and family, people would read each other passages from the Bible, whole novels, or news. As in the case of public readings from the Antiquity, the purpose was first and foremost a social activity.

Penny readings

Oral reading from the nineteenth century thus took place at schools, family dinner tables, labourer’s gatherings, and (to a smaller proportion) in monastic settings—all closed communities. There were however, also readings where the reader did not have a direct connection to the audience. These public ‘penny readings’—named after the entry fees—were closer to a performance, similar to oral storytelling or theatre, with some even including musical accompaniment. Although penny readings were widely accessible due to their low entrance fees, they were a commercial activity and so more limited than a reading in an open public space.

Writing systems

The development of writing is partly responsible for some of the variations in sonority. In periods where support materials were expensive or scarce and when texts were meant for a small group, writing was done economically and thus words were placed next to each other in scriptio continua, without spaces of punctuation. In this kind of transcription, distinguishing one phonetic symbol from another in order to form words and meanings requires an extra layer of manipulation in the mind. It’s much easier to read such a text out loud than in silence (try it for yourself, in figure 1).

Figure 1: Excerpt from The History of Reynard the Fox in scripto continua and spaced transcription, Scripto continua and spaced transcription, Andrea Reyes Elizondo, 2016, CC BY-NC-SA

Graphical cues for creating meaning go beyond word separation. The evolution of punctuation knows a long history in the West: from using a new line for each new thought as in per cola et commata, through the sporadic indication of pauses by points at different heights in a line, to the use of a variety of marks to indicate different types of pauses. As long as texts lacked an elaborate punctuation system and spelling was not standardised, reading in silence was a complex task, while reading out loud was a helpful tool for understanding a text.

Different purposes

As seen above, oral reading has existed since Antiquity, for a variety of purposes, and carried out by different groups. The shift from oral to silent was neither swift, nor progressive. In fact both forms have co-existed until our days, whether in group gatherings, through audio books or reading aloud to ourselves.

Extra credits, images:

Ilsted’s painting – photo by Flickr user ‘Plum leaves’.

Saint Anne from Faras - photo by Stanisław Lorentz, Tadeusz Dobrzeniecki, Krystyna Kęplicz, Monika Krajewska (1990).

Scripto continua image - Andrea Reyes Elizondo.

© Andrea Reyes Elizondo and Leiden Arts in Society Blog, 2016. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Andrea Reyes Elizondo and Leiden Arts in Society Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

1 Comment

Interesting!