Fun, Fitness & Vanity: New Year’s Resolutions on Fiction Reading

'Reading more books' features on many 2018-New Year's resolution lists. But why? For fun, for vanity, or actually for fiction's effects in real life?

Around this time of year, the second half of January following Blue Monday, many people review their New Year’s resolutions. These traditionally involve self-reflection, and the aim to improve everyday habits. It’s therefore interesting that Reading Resolutions, the resolve to read more and/or qualitatively better stuff, have taken a flight over the past few years – and that these resolutions often focus on fiction books. Celebrities like Warren Buffet, Mark Zuckerberg, and Oprah Winfrey publicly share their own reading goals as well as recommendations (the latter two even boast their own book clubs), but non-famous readers are at least as active.

BookTube, the collective of booklovers’ YouTube-channels, is virtually buzzing with vloggers’ self-made resolutions. Many other online communities feature ready-made ‘List Challenges’ you can subscribe to: for 2018, you can take your pick from bulk reading with 52 Books in 52 Weeks, to Reading the Rainbow, selecting your to-reads based on their cover colour – not to be confused, by the way, with the LGBTQIA-reading challenge, that invites you to read books with main characters fit this umbrella term. All this begs the question: why do people resolve to read more books, specifically? And can reading fiction actually improve their life, as they seem to believe?

Me-time and image-building

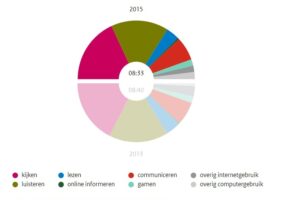

So why would so many people decide they want to read more books? First of all, because readers tend to see fiction-reading as an ultimate leisure activity that they pursue for their own, individual enjoyment. New Year’s reading resolutions could therefore be interpreted as simple determinations to take more relaxing ‘me-time’, especially since (Dutch) adults report ‘lack of time’ is the main reason they don't read more books. Yet resolutions set for this reason don't seem to work very well, as the number of hours spent on recreational reading has been coming steadily down since the 1950’s. In recent years (reports are from 2011-2015), Dutch adults have been spending about an hour and a half reading books – versus an average of a whopping 12 hours per week watching television (fig.2).

Combining the knowledge that New Year’s resolutions tend to evolve around self-improvement with the sneaking suspicion that ‘lack of time to read’ is a ready excuse, it can be inferred that reading is probably seen not just as for fun, but as a desirable activity. Indeed, research suggests that book-reading is partly used as an image-building activity: people like to show, or even show off, which books they buy and read, for instance during their daily commute with public transport. Reading, among which fiction-reading, can potentially connect them with like-minded booklovers and may construct an advantageous image for the rest of their social interactions.

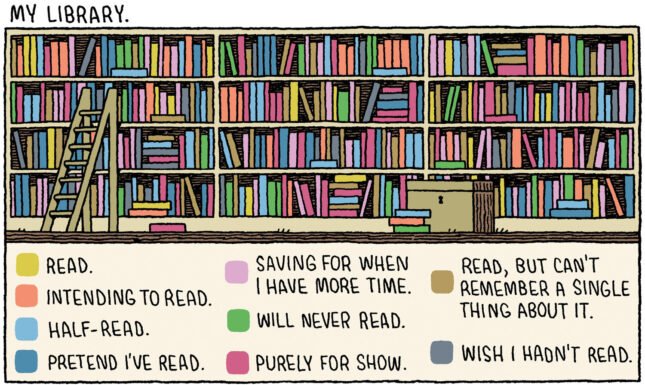

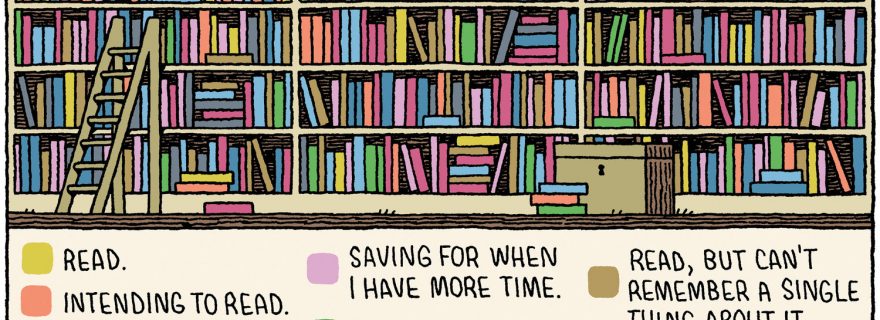

The connotations of reading with wisdom, intelligence, and sophistication are age-old, as is demonstrated by the symbolism of books in portraits. This practice has existed in European art since the Middle Ages, as learned scholars, clerics, and worldly rulers often since had themselves portrayed with a bible and several other volumes to depict their knowledge and acumen (fig.3). The tradition continues, albeit less conspicuously, in our current era: press photos of university professors, politicians, and journalists are still often taken in their studies or in front of their book cases (fig. 4). Want more proof? Graphic designer Erwin Reijers features more than sixty of such portraits on his fun website, 'DeBoekenkastVan.nl’, along with detailed lists of the books that are actually on display! Even young readers on Instagram continue this trend, which they’ve dubbed #shelfie – making self-portraits, not of you, but of your bookshelf.

Is fiction reading good for you?

So is book-reading just a vanity activity, or are there some real advantages to it? Fortunately, there are. The importance of literacy, in general, is widely established, for instance in observed correlations between literacy rates and GDP, or in career perspectives for advanced readers. Literacy is trained primarily through story-reading in education, so in that sense books are certainly important. It’s much more difficult to establish positive effects of leisure fiction-reading on individuals – yet empirical research increasingly discovers its use.

Neuroscience tests show that reading about a situation in fiction, such as a break-up, activates the same brain areas as experiencing it. Moreover, we demonstrably use the same neural networks for empathizing with our real-life social contacts and the fictional characters we encounter through stories. Based on these results, cognitive psychologists such as Raymond Mar and Keith Oatley suggest that fiction reading improves our social skills and empathy.

Reading research based on descriptive, qualitative research through readers’ responses in interviews and questionnaires also confirms the positive effects of fiction reading. Different models of readers’ experience – for instance these frequently-cited studies by Miall & Kuiken (1995) and by Tellegen & Frankhuisen (2002) – outline both intellectual and emotional effects. Pleasurable intellectual effects include, for instance, the reader’s satisfaction in her growing ability to recognize author’s techniques, or plot-orientation. The emotional effects, or the ‘literary response’, are even more important: fiction-reading stimulates experiencing and regulating emotions, as well as a vivid imagination that can even result in the joy of escaping everyday life.

Moreover, reading experience is crucial for either type of effect to occur. Only with experience and habit, built through regular exercise, can readers move beyond a deliberate concentration and get in a state of ‘flow’, also called ‘immersion’, that allows them to forget about the physical and cognitive activity of reading itself and all worldly distractions, and focus just on the story that is in front of them.

These scientific and scholarly conclusions confirm the intuitive notions that avid book-lovers have already harboured for centuries, as for instance presented by famous authors in The Guardian, and eloquently asserted in this speech by author Neil Gaiman:

“And the second thing fiction does is to build empathy. When you watch TV or see a film, you are looking at things happening to other people. Prose fiction is something you build up from 26 letters and a handful of punctuation marks, and you, and you alone, using your imagination, create a world and people it and look out through other eyes. You get to feel things, visit places and worlds you would never otherwise know. You learn that everyone else out there is a me, as well. You’re being someone else, and when you return to your own world, you’re going to be slightly changed.”All in all, reading fiction seems to be a healthy habit that contributes to your cognitive and emotional fitness, much like a work-out helps shape your physique. Add to that that it can even brush up your reputation as a cultured intellectual – what more reason do you need to add a Reading Resolution to your goals for 2018?

>> I’ ve set myself reading challenges, too – and must confess having fallen miserably short of reaching them in previous years. I'm afraid my bookshelves look much like those in Tom Gauld's 'My Library'... But I hope to improve in 2018. Have you set a reading challenge for yourself? Let me know in the comments!

© Fleur Praal and Leiden Arts in Society Blog, 2018. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Fleur Praal and Leiden Arts in Society Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

0 Comments